Kristian Fougner was a 21 year old student at the Norwegian Institute of Technology when the Germans invaded Norway on April 9 1940. He was not exactly an ‘unsung hero’ – his experiences are described in many books written by others about the SIS operations in Norway – but this is the first time his story appears in English. .

In 1947, on his way by sea to the United States he wrote about his experiences during the war. In 2010 his daughter Berit began transferring this manuscript onto her PC. I first met Kristian and Berit at the beginning of 2012 after hearing about him from a Rotary friend. From my notes describing Kristian at our first meeting: ‘Small, wiry, light blue eyes, quick movements, open, much younger-looking than his age, firm handclasp.’ He was quiet at first but quick to answer questions.

His first recollection was of an agent who had jumped to his death to avoid interrogation in Trondheim – “he saved my life.” Kristian came alive when he began to read from his own manuscript; in a strong voice, with feeling and emphasis, like an actor: “Don’t mix with any of the others, said Erik Walsh” – with accompanying admonishing finger pointing upwards and a whispered aside –“I knew Erik Walsh well, (Walsh was Head of SIS in London). I was with him a few days before he died”– in a lower, respectful tone. When I mentioned SOE his eyes flashed as he almost shouted “Bråkermakerer” – Troublemakers – no love was lost between SIS and SOE.

He was able to elaborate and confirm a few details from an earlier meeting and we agreed that when the Norwegian manuscript was completed I should work on it for English speaking readers.

Kristian was very pleased when he read the first part of the English manuscript and, although at the time he was not well, we had a couple of meetings where he positively brightened up as we talked about various episodes. He proved to have a good sense of humour and didn’t take himself seriously. He was reserved but quick to express his opinions – mostly about what he called injustices and failures during the war. There was no sense of bravado when describing his Resistance exploits. The trials and tribulations in Trondheim were simply events that had to be faced up to and overcome. He downplayed his Norwegian award of the Military Cross with Sword and the Distinguished Service Cross from England. The diplomas in his scrap-book were rather crumpled, but he had kept them, in spite of his protestations. Feisty and determined to the end, Kristian died on August 30, 2012.

Kristian Fougner was a fearless, but modest man. He might have described himself as an unlikely hero – but a hero he was. This is the story of his experiences from 1940 to 1943.

1940

Trondheim

The New Year began as the old had ended. Students at the prestigious Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH) were aware of the war in Europe but probably did not consider the possible consequences as seriously as they should. Here and there a voice suggested that Norway could be drawn into the conflict. But it was a lonely voice, a loose idea, and treated as such. True, some of the students had been called up for ‘Neutrality’ guard but apart from this, and the occasional newspaper article about the ‘phony’ war, life in the sheltered, academic world went on normally. Even the voluntary military training programme was treated seriously by only a few. The Easter break came and the ‘Drammen Gang’: Andreas Fougner, Erik Lorange, Rolf Hansen, Knut Bergstrøm, Kåre Reinholdt, Jørgen Sunde and Kristian Fougner Fougner spent some wonderful days skiing in the mountains. Little did they know that it would be their last Easter in a free Norway for five years.

The alarming news may well have been about the British mine-laying along the Norwegian coast. The news of this came on Monday and that evening discussions in the Student Union became heated as the seriousness of the situation solidified. The fracas moved outside to the home of the British Consul where, signalling his sympathies, Kristian writes: Some were for, [The British] others, unfortunately the majority, against. Members of the Student Choir however, including Kristian, gave voice to their convictions by singing the National Anthem; Ja, vi elsker dette landet – Yes we love this country. With these stirring words ringing in their ears they strolled home; in contrast to Koht, extremely concerned about the current situation. Kirstian wrote that these thoughts had been complicated by the news of the sinking of a German submarine off Kristiansand. (Actually it was the German freighter Rio de Janeiro that was sunk by a Polish submarine. Germans in uniform, who said they were on their way to Bergen to “save Norway”, were rescued by local fishermen.)

Tuesday, April 9th, 1940 – Kristian’s account:

None of us who experienced this day will forget it. Sometime between 4 and 5 in the morning I awoke to the steady drone of aircraft. I can honestly say that I realized at once that these were not Norwegian aircraft – not at that time of day. Nevertheless, it took me a few minutes to gather my thoughts and deduce that they must be foreign. In spite of my room-mate Erik Lorange’s scepticism I got up and went to the window; aircraft right enough, certainly not Norwegian but impossible to see which nationality. Switching my gaze from the sky I looked down to the harbour. The two huge warships anchored there probably had a combined tonnage that was greater than the entire Norwegian navy.

My first reaction was, well, there’ll be no exams this year. Then the telephone began to ring. Early that morning, German warships had passed by the forts at Agdenes without a shot been fired. German troops occupied Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger and Narvik. Rumours, which later could be both positive and negative, began to swirl around. Did I understand immediately what was happening? Strange to say, but I am not certain. I understood that our studies would be interrupted, but that we should fight, shoot, perhaps be shot, see our towns destroyed, be occupied, in short that we would no longer be at peace; no, I don’t think I realised this at first.

But already in 1938, NTH students had reacted to the vicious Nazi anti-Jewish pogrom of November 9th – The night of broken glass. At a meeting on November 12, they passed a resolution condemning the action and asking German students:to use all their influence to oppose this tendency in Germany which all friends of the German people follow with sorrow and shame on behalf of European culture.

On April 9th 500 students plus faculty and staff gathered outside the institute. They had a panoramic view of the German ships in the harbour. The expected mobilization call had not come, key positions were already occupied by the enemy and transport services were highly uncertain. Nevertheless, 400 students decided to leave Trondheim; most in an attempt to reach their units in the south, others, some of them with officer training, on skis to the fortress at Hegra or eastward towards Sweden. Fortified by the ‘seasoned’ military students, the Hegra Fortress continued the fight until May 3rd.

After the futile efforts to stem the German tide, students, staff and faculty gradually returned. Their will to resist had not weakened but they had to find new outlets for their passion. NTH has been called: The Bulwark of Resistance. Kristian Fougner’s story is one of many, all individual, but all intertwined and devious; like a spider’s web, with NTH at the centre.

About six o’clock I went down to the town to see what was happening. The streets were comparatively quiet; one or two similarly inquisitive ‘sightseers’ here and there. My first sight of a green uniform clad German soldier in Norway didn’t repel me as much as it did later. On the contrary, I was curious and after a few minutes conversation I learned that they had been at sea for almost two weeks and that they had been in the far north.

As we stood there talking, more and more heavily armed German soldiers came marching down the street. The famous placard ’To the people of Norway’ began to appear on walls and lamp-posts, and as I read its disturbing message, the full realisation of what had happened started to dawn on me.

The custodian’s office at the Institute looked like a fortress on the Maginot Line; hand grenades and machine guns everywhere. The first German troops to occupy Trondheim were fine looking chaps from an elite mountain division. They obviously thought that they had come to a nation that was on friendly terms with them, and their behaviour was as correct as one would expect from professional German soldiers.

In Service

After the first shock and disbelief, rumours and wild ideas spread like straws in the wind amongst the student population. Kristian was registered with the Air Force and standing orders called for him to report to the Aviation Training School – not in Trøndelag, but 500 kms. away in southern Norway. That afternoon he bought a rail ticket – to go to war – and at 3 pm, along with many other students, Kristian started on the journey south. Again, rumours were rife, causing uncertainty and delays; where were the Germans now, was the main valley leading to Oslo occupied already, would the British invade?

After an overnight stop at the cabin of a friend, where he heard Quisling’s ‘demobilization’ speech, Kristian continued his journey and discovered that his Air Force station had been evacuated to the remote air base at Østre Æara. He left the train at Rena and managed to get a lift in a taxi to Osen where, in his own words: I got a lift with some Members of Parliament who were on their way to Nybergsund. Unfortunately I cannot remember their names; in fact, I don’t think they even presented themselves. What I do remember is that one of them said it was a shame that someone like me had to go out to fight. I should have told him that it was his fault that we had to go out and fight, practically with bare fists, against such an efficient German war-machine – and then punched him. However, this wouldn’t have got me the lift. We approached the air station late at night. Road blocks and guards were the visible signs of war. My politicians stopped to talk to the guards. Whilst I stood there freezing, a large caravan of cars arrived – the King and his followers – it was the night between April 11 and 12.

April 12th was a busy day for Kristian. In a way his experience exemplifies the confusion and uncertainty that prevailed throughout the southern part of Norway after April 9th. At an early morning meeting with the C.O., and still in civilian clothes, Kristian was ordered aboard a Tiger Moth to take a message to General Ruge. After a brief course on how to use a parachute he climbed onboard – in full equipment, parachute and all – in front of the pilot, Lt. Tufte Johnsen. He had to admit to a certain amount of trepidation but the weather was fine and the flight uneventful. At the destination he was met with deep suspicion when he asked to be put in contact with General Ruge. The army officers had obviously no idea that the air-school had been moved, one of them was in the process of resigning, and anyhow, it was unheard of for a civilian to meet a commanding General in wartime. Complete chaos was Kristian’s description of the scene. He had to return to Rena with only the promise that his message would be delivered to the General.

Kristian spent the following days in a series of questionable exercises including the ‘Sheriff’s Hunt’– … awonder that it ended well, but with the onset of Spring the air-school was evacuated again; the cadets and instructors were transported to Sweden – the ground staff were to follow later. For a few days Kristian was in charge of a small group of men guarding the telephone lines in the valley – a most pleasant form of warfare. Jonas Lie visited the camp during this time and a group of men from Finland, led by Captain Bjørkmann, arrived along with others who had tangled with the Germans at Rasta. Towards the end of the month Kristian and two others were ordered to Sweden to try to obtain some communication equipment.

Stockholm and Back

So it was that Kristian was in Stockholm on May 1. Here he visited a relation, received news of the capitulation of southern Norway, and carried out some ‘cloak and dagger’ work for the Norwegian Legation that involved a trip back to the Norwegian border. His impression of the Legation pretty much sums up the thoughts of several written and oral comments on the same subject:

…the Legation was terrible, with people running about all over the place disturbing each other. Nobody seemed to know anything and a firm, guiding hand was obviously missing. I saw it all from a very junior position and will not judge, but the working conditions were certainly untenable. In connection with my original task, I received an export licence for field telephones – but not for the cable. Further commentary is unnecessary.

Given his ‘attention to detail’ nature, this was too much for Kristian, and about May 20th he decided to return to Trondheim. Crossing the border was easy – he had only to wave to the German sentry and after a quick body-search for hidden weapons he was on his way. A friendly German driver picked him up at Meråker and he was back at his apartment in Lerkendalsvei 18 on May 23 – the same day that his room-mate Erik Lorange returned. We can only imagine the tales they had to tell each other that evening.

Next day they were back to school … It was a bit strange to have to think abruptly about studying while the fighting continued in Northern Norway. Every morning we heard aircraft leaving the Trondheim airfields on their bombing raids in the north. We had only a week to prepare for the exams but by June 18 we were finished and I could head south for our holiday cabin at Hvaler.

The year continued with the regular progression of holidays, study, and exams and he left Trondheim for home on December 13th. His short summation of the situation in Trondheim gives no indication of what was to come: To be perfectly honest, apart from some, what I considered childish, placards on telephone poles etc., there were no signs of student resistance during that semester.

Again, the first half of 1941 followed the pattern of 1940 but after Kristian arrived back in Trondheim for the autumn semester at the end of July he began to notice changes in the atmosphere.

On August 2nd 1941 the Germans ordered all radios1 in southern Norway to be turned in to local police stations. Kristian’s parents sent their radio up to Trondheim instead, but in the beginning of September the ban on radios was also applied to northern Norway. Kristian removed all the valves from the radio before turning it in. One evening, he surprised his friend Ole Jakob Bjanes at home listening to the BBC news on an illegal radio – and then transferring the news to a stencil for an illegal newspaper. Since Kristian could type at least as fast as Ole Jakob, he was enrolled immediately as a co-worker and member of the group. The production was not large, only about 20 copies, but it was effective; the record elapsed time from end of the news to delivery of the copies was 20 minutes. The recipients were fellow students, neighbours, and teachers, all of whom were known to be ‘good’ Norwegians. Ironically the ban on radios had sparked a demand for outside news which, in turn, spurred the growth of illegal newspapers throughout the country. As Kristian wrote; …Perhaps it wasn’t such a great, or even a necessary operation, but it gave those involved a certain amount of satisfaction in having done something for the resistance, however small. When describing this during our first meeting he commented: “Just boys’ stuff – no heroics.”

The ‘small stuff’ took place almost every night, but it didn’t take long before Kristian realized that his friends were involved in more important activities than a simple news bulletin. That’s why he was not surprised when Ole Jakob, who was ill at the time, was arrested during a razzia along with Bård Hjelde. Both were later murdered in Natzweiler concentration camp. Fellow students, Welle Strand, Bjørn Rørholt, Håkon Sørbye, Nico Selmer and Tore Five avoided the Nazi net and escaped to continue their resistance work.

Kristian and his friends thought that perhaps Ole Jakob’s arrest was connected with the illegal newspaper, so they decided to continue their work to give the impression that he was not involved. They soon found out that he had been arrested for something far more serious –and with fatal consequences. Nevertheless, their illegal news-service continued throughout the autumn semester but towards the end only Kristian and his cousin Andreas were involved. In November, Jørgen Sunde and Kristian were elected as President and Vice-President of the Student Union but they realized that, under the Nazi regime, its existence as a free, independent organization would be short-lived.

1942

After the Christmas break, Kristian and Andreas continued their illegal newspaper work. In their absence, however, bigger and better news-sheets had sprung up so they decided to close down after about 14 days.

At the beginning of February, Knut Alming asked Kristian if he could do some small jobs for him.Doubting Thomas, as Kristian called himself, was hesitant at first but soon said yes. His job was to take some sketches of German positions around Trondheim and find out which troops, and how many, were stationed in the various camps. In addition, he was to recruit a few reliable friends to help him with this work.

Kristian and his friends were happy to be part of a serious intelligence organization and they set about their task with great enthusiasm. In retrospect he realizes that these first activities were dilettantish, to say the least: We were amateurs; nobody dreamed of telling us what we should look for, what we should report. As a result, our reports detailed much trivia, while ignoring important facts. Their work was, however, extremely important and though they did not know at the time, they were actually part of the growing XU organisation2.

On March 23rd Kristian jokingly suggested to Knut that one of them should take a trip to England. Much to his surprise, Knut calmly asked if Kristian would be willing to make the journey in connection with a special plan. After a short pause, Kristian said yes. A couple of days later, Kristian met the man behind the plan and who had organized the trip, Bjørn Rørholt: … the fellow NTH man who had left for England six months ago. He was the same happy warrior he had always been. He toyed with his revolver, puffed out smoke-rings, and showed off his transmitter – the first small Polish radio I had seen. Rørholt’s plan was code-named Babysitters.3 The ‘baby’ was the feared German battle cruiser, Tirpitz. 4

The plan was that five men should be sent to England to learn Morse and basic radio practices. On their return they were to be situated around the Trondheim fjord to help Magne Hassel at Agdenes in keeping tabs on German warships based in the fjord. Kristian was to be in England for only a short time so that his absence would not be noticed. As a further safeguard he was to tell all his friends that he was going away to a remote mountain farm for a well-deserved break from studies. He visited a farmer and arranged for him to send some pre-written letters and to tell any casual visitors that Kristian had gone for a long trek into the mountains. Kristian spread the news of this ‘holiday’ among all his friends and relations. Again, he had to admit: …I was more than a little impressed by all this important activity I had got myself into.

To England

The five ‘babysitters’ were: Kristian, Hugo Munthe Kaas, Arnfinn Grande, Halvard Gabrielsen and Kaare Nøstvold. The trip to England didn’t work according to plan. Their first attempt, from Frøya, had to be aborted because of bad weather. After a few days back in Trondheim they set off for Kristiansund, officially on their way to Bergen, but actually to Brattvær, with the rather unlikely story that they were surveyors for a German defence project. The locals tried to bribe them to report that the island was not suitable for this purpose but the ‘surveyors’ went to the western side of the island, supposedly working, but actually scanning the seas for their boat. When they finally saw a fishing smack heading towards the pier they were certain that this was it. A voice with a broad Bergen accent – …are you the ones wanting transport? confirmed their hopes. As the boat tied up at the pier the local population gathered around. Onboard were several bags addressed to Bjørn Rørholt in Trondheim. One of the locals was to deliver these. With the important cargo offloaded, the five men went aboard: the real adventure had begun.

It was a heady feeling: To stand on the deck of a free, Norwegian vessel, surrounded by Norwegian sailors – what a wonderful setting for April 9 1942 – exactly two years after the infamous Nazi invasion.Those who remember the food situation in Norway at that time will not be surprised to hear that the first thing we did was to fill our bellies. Then a smoke after which the first sea-sick victims retired. Then a talk with the men onboard – though they had been back and forth to Norway regularly, they were still anxious to hear the latest news. The man with the broad Bergen accent, the skipper, was Leif Larsen, later to be known and famed, as Shetlands-Larsen. He was a fine specimen of a man; calm, cool, pleasant, and easygoing. We were treated as honoured guests – as far as this was possible on a simple fishing smack, in rough weather on the North Sea. Rough weather or not, I managed to remain remarkably free from sea-sickness and the journey, except for a close-call with a floating mine, was uneventful.

The weather delayed their entry to Luna until April 11 but their first impressions were no less overwhelming: We went around in a daze, just to be able to read English newspapers, hear the news, eat what we wanted, and most important, to know that we were in a free country. They didn’t get much time to savour these sensations. Later that day they were driven to an airport south of Lerwick where a Dakota, carrying Lt. Cmdr. Eric Welsh, landed and prepared to take them south to the mainland. En route, Kristian began using his school Enlish to talk to Welsh and the Commander allowed him to rattle on for quite a while before replying in perfect Norwegian with a broad Bergen accent. Welsh had lived in Bergen for several years as the representative of a British chemical company! They spent the next night in the officers’ mess – and Kristian continued to be pleasantly impressed by all the fuss they were creating.

Next day, another journey this time to Hendon Airport near London: It was a brilliant day and a fantastic trip. The things that impressed me most were all the airports we flew over and the aircraft that buzzed around us all the time. After a few days in London the men were moved into a house in the country to avoid the possibility of meeting people who might recognize them. The house was ‘home’ to many similar strangers to England and in charge was ‘Mamma’, a portly woman who looked after her charges like a mother hen.

The men were driven daily to and from the school where they practised the Morse code – almost to the total exclusion of any related subjects. After 14 days Kristian managed to reach the required speed to qualify for the return home – and had also picked up a smattering of radio operating, coding, and German ship recognition. Their instructors were Lt. Cmdr. Welsh, Lt. John Turner and Lyder Larsen. The only Norwegian officer they met was Major Nagel, head of the ‘E’ (Intelligence) office. Kristian had scarcely time to register any impressions of England but from the little he saw he realized that London had taken a beating and … was already beginning to look shabby and worn …The few Englishmen I met, in addition to those already mentioned, made me feel enthusiastic about the country.

Trondheim again

Kristian didn’t get much equipment to take back with him: A Polish radio like the one recommended by Bjørn Rørholt, a large British ‘crap’ Mark V radio, some chocolate and some cigarettes. The hopeless British radio he left with an understanding John Turner and on May 5th he left London by train to Inverness and continued to Lerwick by plane. Next day he left Luna, this time without companions, but with the same skipper, Shetlands-Larsen. The voyage back was calm and peaceful and only later did they learn that planes had been sent out to look for them and warn them to return as there had been a razzia at the place they had planned to land in Norway. Kristian was thankful: Luckily they didn’t find us, he wrote.

Early in the morning of May 9th they approached Vindholmen, just north of Brattvær. The crew craved some Norwegian salmon so they berthed right inside the harbour and a couple of the men, with Kristian and his suitcase in tow, strolled up to the village shop. Kristian was troubled: They didn’t even bother to take off their uniforms. There was no doubt that they were in the Norwegian Navy. They got their salmon and after a while I was left standing there with my suitcase. I must admit I didn’t feel exactly on top of the world – I might as well have had a baggage tag tied to my hand – Handle with care, just arrived from England. But there wasn’t much I could do about it. I rather wished that I had been onboard again as I saw the boat disappearing over the horizon. His depressed state wasn’t improved when, a couple of hours later, he boarded the Coastal Steamer and asked for a single ticket to Kristiansund. The sailor looked at him as he took the money and in a low, quiet voice said: This is cheap for such a long journey. Kristian thought, So much for anonymity! After a night in Kristiansund he travelled by bus to Trondheim and was back in his apartment late that evening.

To say that my appearance caused a certain amount of surprise is an understatement. That very day, three things surfaced that upset his well-set plands: His apartment had been requisitioned, his landlady didn’t believe the story of a country life chopping wood, and worst of all, he learned that a couple of his girlfriends had moved heaven and earth to try and get in touch with him while he was away – even to the extent of making a trip to the alleged ‘farm’. Kristian thought that the situation was grim – stopping the girls from talking and destroying his alibi wasn’t going to be easy. However, he found a solution and spread the story that he had spent the entire time with a girlfriend in another remote cabin. A shocking disclosure in those days, quite the normal daily routine today!

The day after his return, the National Socialist Party (NS) had convened a meeting, with compulsory attendance, in the Student Union. The speaker was NS County Commissioner Henrik Rogsted. Kristian, Erik and Knut sat on the first row: We must have looked charming – if only they’d known, was Kristian’s comment.

His first problem was to find a place to live but he had a temporary roof over his head with XU-agent Erik Storsveen. On the evening of May 12 he rigged up his antenna, tuned in his Polish radio sender and sent out his first call sign as an SIS Radio Operator from Station Leporis. It was an exciting, nerve-racking moment, but: After a short time I suddenly heard some signals and from my list of call-signs I knew I had contact with Home Station in London. Now I might have said – ‘and thus the traffic began,’ but to be honest, I was so exulted in making contact that my reply was, to put it mildly, awful. Errors and nonsense – the guys on the receiving end must have been cursing me till the sparks flew.

It is interesting to read Kristian’s own words concerning his first messages. They show the scope of his task and point out one of the problems – British scepticism about intelligence from Norway: My first messages were about the failed air attack on Værnes airport while I had been in England and about ‘Prins Eugen’ which had left the harbour a few days earlier. The next time I was in England I learned that P9 5 had received the messages about ‘Prins Eugen’ but nobody in the Admiralty believed the information. It was only later, when aircraft reconnaissance recognized the ship off Jæren that an attack was launched against the ship. Kristian noted that…after this, the Admiralty began to trust our information.

Kristian’s housing problem was solved when he moved into the apartment of one of his colleagues who had left for Sweden. The apartment was ideally located for transmitting and making contact with ‘Home Station.’ His ‘code name’ was ‘PELLE’ and he worked directly with the Intelligence service (E-service) leader team, Erik Storsveen and Knut Alming, (‘Truls’ and ‘Oscar’). In addition these messages and his own observations of ships’ traffic, Kristian was the radio link for ‘XU’, the intelligence organization founded by Erik’s brother Arvid in southern Norway. At that time however, Kristian: didn’t know anything, nor did I want to know anything about the ’XU’ organization. We always worked on the principle that the less you knew, the safer you were.

This was a busy time in Trondheim. The German battleship ‘Tirpitz’ and the battle cruiser ‘Hipper’ were a constant threat to Allied sea lanes and Kristian had orders to report on their movements – preferably daily. He describes one typical day: First contact with Home Station either 6 am or 7 am, usually in contact for about 30 minutes. Then breakfast and off to school. As I approached the institute I saw ‘Grandfather’ and ‘Grandmother’ heading full-speed seawards. About turn and home again to encode a telegram, make contact and transmit. Then back to school – but by this time the ships might be on their way back in, so home again, encode, contact, send – it could happen a couple of times a day.

Usually, the Home Station asked for specific information about the ships’ bases in the Lofjord and Aasenfjord, their locations and the state of their torpedo nets. Towards the end of June it was obvious that the TIRPITZ was preparing to go to sea. She had done this once before without being reported. The TIRPITZ was the most effective battleship ever built up to that time and the Admiralty had to keep comparatively large elements of the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow in preparation for a possible break-out. They even sent ships cruising just outside Norway’s 3-mile limit in an attempt to lure the Tirpitz out of its safe haven. Kristian and his colleagues didn’t know the whole of this story at that time but they knew that the more information they could send about the ships, the better the Admiralty would be able to contain them. To this end, Kristian, Bjørn Eriksen and Knut Alming organized a 24-hour watch on the ships that lasted until the end of July.

Kristian writes about the SIS radio stations in Trondheim: In addition to my station (Leporis) we had a transmitter in the Agdenes fortress manned by Magne Hassel (Lerken 2) , and another one attached to the Lystad group (Scorpion) manned by Knut Jacobsen. When it began to look imminent that the TIRPITZ would leave, we advised Home Station and tried to put a 24-hour watch on the ship. Bjørn Eriksen took this task and I will have more to say about him later.

In the middle of all this activity, Kristian had to leave Trondheim to take his Diploma Exam. Gunnar Hundal, from Levanger agreed to take over the transmitter while he was away but Kristian continued to send messages until the last moment. Two days after he left Trondhiem, the TIRPITZ steamed out of the Trondheim fjord.

What was it like to be a radio operator hiding away in one of the most important towns of an enemy-occupied country? Kristian writes: Apart from the first few days everything went smoothly and I can only remember a couple of nervous moments: Once, in the middle of a transmission somebody knocked loudly on my door. With my heart in my mouth and pistol cocked, I opened the door – to find a school friend who didn’t realise how close to death he had been. Years later, after the war, when I reminded him of this episode he said that he did think I was a bit unfriendly on that occasion but he had no idea of what was happening in my apartment. On another occasion, the man in apartment next to mine, who had an ‘illegal’ radio, switched on to hear the news from London just as I was in the middle of sending an important message. I jumped up, banged on the wall, and shouted for him to turn off his noisy radio. He did so, but was a bit surprised by my violent reaction. After that, we agreed that I would avoid transmitting when the news from London was on the air. Otherwise, I never had the slightest suspicion of being monitored. And this, in spite of the fact that Kristian had been transmitting from the same place every day.

After a summer of exams and holidays with family and friends, Kristian returned to Trondheim in September. In the luggage rack above his head on the train was a new, improved, but just as big and heavy, Mark V transmitter. Again, his journey was uneventful.

His arrival, however, was problematic. The man who had taken over Leporis had failed to make contact with Home Station, and, once again, Kristian had no place to live because Eric had also returned to Trondheim. Eric’s apartment was perfect for a secret radio station. Kristian had rigged up the new set there upon his arrival and made contact immediately. Finding a suitable replacement was impossible. Kristian had to move in with some relatives, one of whom was a doctor at Ringvål Sanatorium, just outside Trondheim. The new radio station was code-named Virgo.

Erik Storsveen and Knut Alming, had agreed with Kristian that he should take charge of the radio operations in Trøndelag and be a “trouble shooter” for the organization. This would have been a comparatively easy task if he had been in Trondheim itself, but travelling back and forth to Ringvål made things extremely difficult. Neither were the transmitting conditions favorable at Ringvål and his equipment had to be locked in a cupboard every day. During the whole of October he made contact only a couple of times. Transmission at night were almost impossible, he tried every evening for three weeks without contact. Thus the month went by and he had been unable to begin his task as “trouble shooter.” On Friday, October 30, 1942 his small world collapsed.

Razzia

At 0945 the janitor came in and waved him over. Kristian sensed that something was wrong. The janitor told Kristian that he should go immediately to professor Sundby’s office. Almost before the janitor had finished his message, another student rushed in and said that the Germans, in full force, machine pistols cocked, had been looking for Kristian at his previous apartment. Professor Sundby said that he had greetings from Knut who had had rather an uncomfortable morning but was now safe – in the professor’s keeping as Kristian learned later. They agreed that it would be wise for Kristian to lay low for a while, even to take a little holiday! He would get more information when he went to a certain address that evening.

Kristian’s next thought was for the radio equipment at Ringvål. He got fellow student Svend Øren to cycle as fast as he could to get the suitcase from his room. Svend set off – but was too late, the news that Kristian was on the run had already reached Ringvål. His relatives had been suspicious of the suitcase, opened it, and in desperation knowing its potential danger to them, they threw the transmitter into a swamp. Exit Virgo!

Kristian then left the Institute as fast as possible. He was still unsure of Knut’s fate and had time to kill until the evening meeting. However, by midday the news was all over town. The Germans thought they had wounded him. They issued orders to all doctors to report anyone seeking help. Knut himself originated rumours about the escape; his clothes had been found by the river bank, he had drowned himself. Everybody believed he was dead. Nobody thought about anonymous Kristian: Not many people knew that the Germans had been searching for me. I passed the time by walking around and went to a German cinema – the only time I was at the cinema during the entire war. At the rendezvous that evening I was given an address in Biskop Wechselsens street – a street I’d never heard of. It took me a long time to find it but finally I arrived and met Thora and Johanna Matheson6 . Erik Storsveen was there too. Although the Germans had not been looking for him he thought it best to disappear – at least for a while.

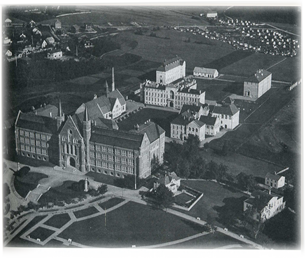

NTH Trondheim 1939 (Tapir Forlag)

As they sat and discussed future plans Kristian also learned what had happened at the Institute that day: About midday, the Germans cordoned off the whole area. They ransacked every building, arrested all the students in Kristian’s class, and sent them to Vollan prison camp. All except one, who was later sent to Sachsenhausen, were released by the end of June. From the material they found at Knut’s apartment, the Germans realized that they had stumbled upon an important group. Luckily, nobody who could have told them anything had been captured and the leaders were free and clear

Kristian and his ‘babies’, however were in disarray: Virgo was destroyed and Leporis remained silent. The Leporis operator tried incessantly but Home Station complained that they heard nothing. I only discovered the reason for this on my next trip to Trondheim

Escape

Kristian and Erik decided to leave immediately and to cycle the first part of the journey to Stockholm. A slight problem was that Kristian had no bike. He first tried to borrow one from a relative who adamantly refused and slammed the door in his face but his second attempt at a friend’s house was successful. Another problem, that he was hardly dressed for cycling, was solved by helpful friends who provided rubber boots, an anorak and a backpack. They left at 11 pm, October 30th, not knowing whether or not the roads were blocked by German patrols. A colleague agreed to drive them the first part of the trip. German patrols were, indeed, searching for them but the guards at the only blockade they encountered let them by unhindered. They were lucky – a blockade further along an alternative road, had received descriptions of both men, trains were being searched: we had the honour of being at the top of the German list of wanted men.

It was a brilliant night, with little snow and glittering moonlight. They stopped at the Morseth Farm for a few hours’ rest. Two couriers on their way to Trondheim dropped in as they sat eating breakfast next morning. The farm, a hive of illegal activity, was soon to become the scene of a great tragedy.7 Tormod Morseth arranged for them to ride in the back of a truck on the next stage of their journey. After another two days, partly on foot and partly on skis, in pleasant weather, biting cold and raging storm, sleeping in the open and breaking into cabins, they crossed the border on November 2nd.

Sweden

Next day they reached Storlien and boarded the train that would take them direct to Kjesæter, the reception center for Norwegian escapees. After only a short distance however, Swedish police stopped the train, took them off, searched them and put them in a cell in Jarvan. They were kept there for two days. Kristian was not at all happy: The windowless cell was 2 by 1.5 metres. I have rarely been as angry. The Swedes were as overbearing and arrogant as only Swedes can be. They asked us why on earth we hadn’t stayed in Norway and taken the mild, justifiable punishment the Germans would have given us. Surely we didn’t believe all the hate propaganda about the Germans? If we didn’t tell them everything they would send us back to Norway under escort. All in all, the reception we got from the Swedes was thoroughly pathetic.

He continues: Our next stop was Østersund County Jail. The cell was bigger but not much better. Well, Saturday evening was quite entertaining; when the town’s drunks were thrown in jail all hell broke loose, but it was fun. On Monday morning I was released but Erik had to sit there for two more days. Adding insult to injury, I was presented with a bill – they had found 200 Swedish crowns in my wallet and charged me Skr.6, 75 daily for the pleasure of being in their jail – again, pathetic!

Kristian finally arrived in Stockholm on November 11th and made his report on the situation in Trondheim to Major Dahl in MI 2 who pulled the necessary strings to get Eric released. Kristian returned to Kjesæter next day where he met both Knut and Erik and they all went through the usual control and refitting process.

On November 14th they returned to Stockholm and spent the next weekw writing reports and congratulating each other on their tremendous luck. Erik returned to Trondheim and after a few days Kristian and Knut got orders to return to England. Which was easier said than done, space on the air transport to England was at a premium and, as Kristian wrote about waiting: There’s nothing quite as destructive of morale as uncertainty. While they waited, they had time to think about how the Germans had got on their trail. In Knut’s case, the first clue was his name written on a slip of found on a man they had arrested in Oslo; Knut had had contact with this man in 1940! At first, the Germans simply wanted to check out the name and only after the evidence they found in his apartment did they realise that he was actively engaged in Intelligence work. As far as the suspicion of Kristian was concerned, it was a mystery; he hadn’t lived at the place they came looking for him for six months and even though they knew he had moved to Ringvål they never went there and never questioned his host family. Kristian concluded that: … they couldn’t have had any serious suspicions about me – but I didn’t know this at that time.

London

Not until December 16th did Kristian and Knut get seats on the flight to Leuchars in Scotland. They landed next morning and took the first train up to London where they checked into the Norwegian center, now relocated near Putney Common. Here they found old friends, caught up on the latest news and relaxed in the large, comfortable house and its English garden.

Knut Alming, Jon Brynildsen, Krinstian Fougner

Putney 1944

At the Norwegian Section Office in Lancaster Court, Commander Welsh was happy to see Kristian again. They quickly agreed that he should make another trip to Trondheim. Since Kristian’s departure, London had heard nothing from his radio station Leporis and Trondheim was, in fact, a closed book at that time. Sea traffic to the Trondheim area had been suspended so Kristian could look forward to a parachute drop for his next visit. His objective was to get Leporis back on the air and return immediately. Thinking that perhaps the reason for the breakdown in communication with Leporis was technical, Kristian took a crash course at the section’s Radio School. Here he learned elementary technical repair together with: …the strangest people: French, German, Canadian and many other men and women of uncertain nationality. Personally, Kristian was keen to

negotiate a closer cooperation between the regular British Intelligence in Norway and XU – which came under another department. Arvid Storsveen, who was in London at that time, had put new life into the cooperation between London and Norway. Knut and Erik started to work with him and agreed to co-operate with Kristian’s Virgo II operation. They gave him some XU contacts in Trondheim who could probably accommodate him for a while. He had some messages to take with him to XU, but had no idea who had been installed as the new leader in Trondheim.

Kristian and his colleagues celebrated Christmas Eve 1942 in Putney, a strange affair with half-drunk comrades, Christmas tree, ‘Mamma’ in her best outfit and tears in her eyes; a memorable evening indeed.

1943

By the beginning of January Kristian had almost completed his ‘radio education.’ On January 17th, together with a Dutch agent and an SOE officer he headed for Ringway airport, near Manchester for parachute training. They stayed at the SOE officers’ quarters in nearby Wilmslow. This was to be his first parachute drop and he comments, laconically: I was there several times later but my first impressions of the noble sport of parachute jumping remain fixed in my memory.

Training began next day, Monday. Kristian and the Dutchman were the only pupils so the instructor could drive them pretty hard: gymnastics, falling techniques, exiting the ‘plane, putting on, guiding, landing and re-packing the parachute. Exhausting work to say the least and next day, the day for the first jump, it seemed as though every sinew and muscle in Kristian’s body ached. On the way to the airport Kristian began to regret that he had ever agreed to a parachute jump, and his courage sank in proportion to the distance from the airport. But there was no turning back. Ringway airport was infested by men training to be parachutists – from those who had never jumped before to instructors who had jumped hundreds of times. When Kristian returned for the last time in 1945 the record holder had jumped over 1000 times.

Kristian writes: We followed our instructor like lambs to the slaughter to pick up our parachutes. (“If it doesn’t work, bring it back and we will change it for you.”) Amazing how little one appreciates this kind of humour in such a situation. But in 1945, when I had heard the same joke for the umpteenth time, I began to see the funny side of it. In two days of mixed emotions, through fear, suspense, exhaustion, to relief and joy, Kristian progressed from novice to, if not expert, at least experienced, parachutist with three daytime and one nighttime jumps to his credit. On Thursday morning he returned to London.

Flight back to Norway

Life in London was hectic as he packed his rucksack and selected his skis. He was sent to a theatre make-up artist: a sweet little lady who attacked my eyebrows with supreme contempt. After two hours the work was completed and a disguised Kristian appeared. On Saturday January 23rd Kristian was driven to Tempsford airport, the top secret base for SOE operations.8 Here he received his personal effects – jumpsuit, reserve provision, torch and: not to forget my little flask filled with whisky. He was then driven up to the officers’ mess to wait. It was not unusual for agents to have to wait for several weeks for their flight but, again, Kristian was lucky, at precisely 1900 hours his 4-engine Halifax aircraft appeared on the runway.

The flight time was expected to be 5 hours and Kristian snuggled down in his sleeping bag to get some sleep. Here’s his description of the flight and arrival in Norway:

To say that I slept would be an exaggeration. No, I must admit that I lay and thought about what was to come. First the jump, and then what would I find in Trondheim? The trip over the North Sea and the coast of Norway was uneventful. It must have been about 0100 hours when they woke me and said: 30 minutes to go.

It was a brilliant night; Norway lay beneath us in sparkling moonlight. However, I can’t say that the way I was to land on Norwegian soil again appealed to me. After 15 minutes, the exit hatch was opened and a gust of ice-cold air surged into the cabin. On top of my personal misgivings, the cold air made my situation even more uncomfortable. When the order ‘Running In’ was given, I looked down – luckily – for below, instead of glittering snow; there was a black void. Shouting and using sign-language I managed to tell the dispatcher that I couldn’t imagine a less likely place to jump, and after contact through the intercom the pilot agreed to search for the correct Drop Zone(DZ) – Samsjøen. There, in the mountains, I was sure that there would be ice on the lake that I could see from the aircraft. Our present position was obviously incorrect. (In 1945 I met the Intelligence Officer who had de-briefed the crew. He said that when I refused to jump, we had been over the fjord outside Orkdal!) I sat there, on the edge of the hatch, for 45 minutes while the pilot searched for Samsjøen – it wasn’t the most comfortable position. Finally the new ‘Running In’ order came. This time, at least, there was snow below and I started to get ready to jump with a so-called ‘C-parachute’ i.e. with my supplies packed between me and the canopy. My skis, with their own parachute, would then follow. The two dispatchers had difficulties with my supply package which began to rotate and twist the cords. ‘Red Light’ – Action Stations – the aircraft slowed down. I was frozen stiff, inside with excitement, and outside from sitting so long on the edge of the hole. Green Light – I was almost half-way out of the hole before I felt the slap on my shoulder and heard GO! As I entered the slipstream I felt as though I would be blown to bits. I turned a couple of somersaults, heard a scary ‘rip’ from above but finally felt myself swinging safely. I had just about reclaimed my senses when I saw a dark shadow flash by. Shortly afterwards I heard a crash from below. My skis had fallen rather faster than expected and I never saw them again. Now it was time to prepare for landing: legs together, slightly bent at the knees, pull the head between the arms and look down. But what was that – a point of light shining straight up towards me. I wasn’t expecting a reception committee so a light down there could not be anything positive. It was difficult to believe that I was so unlucky. However there was another explanation: Before leaving I had been issued with two torches which should have been in a pocket in my jump-suit. I checked, but one of them was missing. Somehow the other one must have fallen out when I jumped, and landed in the snow, switched on and pointing upwards – there’s no other explanation. The night was still sparkling clear and I had no difficulty in seeing the area below. I was heading straight for a large white patch. I landed at the edge just beyond some trees and was dragged onto the white patch – which turned out to be Samsjøen. I began to release the harness and was almost free when I remembered the supplies above my head. The wind was pretty strong so I had to hang onto the cords of the canopy and was dragged all the way across the lake on my stomach. When my involuntary journey ended I could breathe easily again and was just in time to see the aircraft before it disappeared over the mountains. I flashed the ‘OK’ signal with the torch and looked at my watch; it was 0215, Sunday January 24 1943. As I sat there collecting my thoughts and making my plans, the thing that impressed me most was the silence. The only sound was from a river about 60 yards from where I sat; quite a big change from noisy London via a roaring aircraft to a peaceful Norwegian mountainside. It took a while for me to orient myself and to be sure that my frozen lake really was Samsjøen. Then I had to get rid of the parachute; everything was frozen except the river so that’s where most of it ended up. I kept part of it in case I had to sleep outdoors on the way to Trondheim and while sorting all this out I found a meter-long rip in the canopy. That must have been what caused the ‘ripping’ sound I heard just after leaving the aircraft.

Trondheim again

Kristian’s original plan was to get away from the DZ on his skis as quickly as possibleso that he could head directly to Trondheim and enter the city with the returning Sunday afternoon skiers. Without skis he couldn’t avoid leaving tracks in the loose, deep snow, so he had to get to a built up area as quickly as possible. After a strenuous 4-5 kms trek he came to the cabin of the dam guard where he rested and got a bite to eat. The guard told him about the aircraft he had heard during the night but otherwise made no comment about Kristian’s presence, without skis, in such an out-of-the-way place. The guard showed Kristian the way down to the station and agreed that it would be best for him not to talk about his unusual visitor.

Late that Sunday afternoon Kristian sat in a train crowded with Germans, Norwegian ‘Quislings’, and farmers heading towards Trondheim. It was dark when he arrived. He felt strange being in Trondheim again; the events leading to his departure being fresh in his memory and all his friends believing him safely out of the country. The first of the contacts he had been given before leaving London had left Trondheim but extremely late that night he found the alternative, Oddmund Solberg, who was able to put him up for the night.

The next morning, January 25th, Oddmund, Kristian, Gunnar Hundal (Leporis) and Bjørn Eriksen,(head of XU in Trøndelag) met to discuss the situation. Kristian judged that the Leporis station was poorly located and that the antenna was incorrectly aligned. He took the transmitter with him to a new lodging with relatives of Oddmund, who lived at Singsaker. This was not exactly the best neighbourhood because Kristian had lived there and people might recognise him. It was also a hopeless location for radio transmissions.

The next two days were unsettling for Kristian. On Tuesday evening he and Bjarne Østensen had a long meeting in Bjørn Eriksen’s apartment. Bjørn Eriksen talked generally about his tasks and was clearly uncertain of his ability to head the Intelligence Services. In fact he appeared a bit disturbed, but when Kristian asked him if he had discovered any ‘leaks’ or other insidious incidents he replied emphatically no! He also insisted that he always destroyed all incriminating papers. Kristian tried to calm him and said that if he noticed the slightest sign of German interest in him he should go underground immediately.

In Kristian’s words:… this would be absolutely the best thing, both for the organisation and for himself. Furthermore, I tried to imprint upon him Welsh’s maxim: LITTLE, BUT GOOD. My own experience confirmed the truth of this nugget of advice. It takes such a long time to build up an organisation that it is better to sacrifice one man than to compromise the entire group.

I think I was able to make him realise that he was as competent a leader of the Intelligence Service as any other. He, in turn, assured me that he didn’t believe he was in any danger. Mutually assured, and discovering that his room was ideal for radio transmission, we agreed I should come back next morning to send some messages to London. I left him just before midnight.

Earlier that day Kristian had met with Knut Siem Knudsen who had established two stations in North Norway. He was even more nervous than Bjørn. He jumped at the slightest sound and became almost hysterical when a car drove by. Kristian remained calm and unaffected. He firmly believed in his own ‘lucky star’ and was convinced that nothing could possibly happen to him.

Next morning at 0730, with the transmitter in his backpack he arrived at Bjørn’s as agreed. Bjørn was supposed to open the door at this time so that the others in the house wouldn’t see Kristian. Eight o’clock came, but no Bjørn. A man came out and asked Kristian what he wanted. When he told him, the man gave Kristian a strange look and said that the Germans had been there just after 0700 and taken both Bjørn and his brother. Kristian couldn’t understand why the Germans hadn’t posted a guard at the house. My lucky star again was all he could think.

Kristian had no idea why Bjørn had been arrested but he reasoned that he himself couldn’t have been the cause. If the Germans had known about Kristian they would have let him lead them to all his contacts rather than arrest just one of the earliest – Bjørn. And so it was, the Germans didn’t know about Kristian. Bjørn had been arrested because of information gained from the arrest of another man in the same group.

Mission Hotel Trondheim:

Kristian’s only thought now was to report to England and to ask for fresh instructions. But first he had to find somewhere to live. He began to make the rounds of contacts and at the second call he received another shock: Bjørn had thrown himself out of a window on the 4th floor of the Mission hotel – the Gestapo headquarters – in Trondheim. The first report said that he had been sent to a hospital and was unlikely to survive. Kristian and his contacts agreed that they should lay low until they could find out how much information the Germans had forced out of Bjørn before his suicide. As far as Kristian knew, another ‘razzia’ could start anytime.

Kristian’s only thought now was to report to England and to ask for fresh instructions. But first he had to find somewhere to live. He began to make the rounds of contacts and at the second call he received another shock: Bjørn had thrown himself out of a window on the 4th floor of the Mission hotel – the Gestapo headquarters – in Trondheim. The first report said that he had been sent to a hospital and was unlikely to survive. Kristian and his contacts agreed that they should lay low until they could find out how much information the Germans had forced out of Bjørn before his suicide. As far as Kristian knew, another ‘razzia’ could start anytime.

And, once again, Kristian was homeless – he couldn’t stay with anyone who had had contact with Bjørn so Oddmund had to fix something away from the centre of the town. Unable to set up his own transmitter, Kristian had to resort to using the XU network. He tried, but was unable to make contact with one of the other ‘babysitters’ (Lark II at Agdenes) and ended up relaying messages via another Trondheim station, ‘Scorpion’.

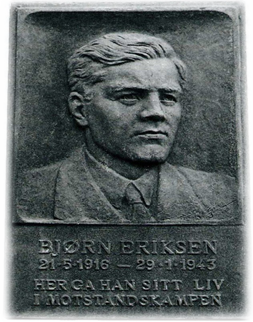

Memorial Tablet outside Mission Hotel,

now Hotel Augustin (Tapir Forlag)

On Friday, January 29th, only five days after Kristian’s arrival in Norway, the Scorpian operator, Siem Knudsen, suggested that Kristian should leave Trondheim as soon as possible. Kristian agreed – the lodging problem alone made his situation impossible but later the same day he regretted his easy acceptance of the suggestion. Instead of leaving he took a bus down to his relatives in Ringvål where he had stayed on his first mission. None of the family recognised the disguised Kristian. His aunt was ill and his uncle was clearly shocked when he realised who the unexpected guest was. Although Kristian could only spend one night: …it was wonderful to sleep in a comfortable bed in such a peaceful place. The next day he rigged up his antenna, tuned in his radio and was immediately able to send his reports to London. In the evening he returned to Trondheim and during the next two days he was in contact with London several times even though he had to change lodgings each night. His colleagues were nervous after Bjørn’s arrest and suicide and Kristian did his best to calm them by saying that new instructions and personnel would be coming soon. In the meantime: I told them to take it easy and don’t make any waves. Kristian himself, however, was not spared the general unease and uncertainty. He thought that the Intelligence service in Trondheim should become inactive for a while and he discussed this with the local radio operator Storvik who agreed with him. During these two days, Sunday and Monday, Kristian mulled over his options.

In retrospect he wrote: I…took a decision that I have always regretted – that it was best for me to leave Trondheim.

In my opinion, this expedition was fairly unsuccessful. Many times since then I have bitterly regretted my decision to leave. On the other hand, when I look at it with the hindsight of the experiences from my time in London, I must say that it was probably the right decision after all.

There is no doubt that things had begun to heat up in Trondheim and there were too many people who knew I was there. If I need an excuse, it is that I never found a suitable place to stay. The constant flitting created increased security risks.

And then there is Bjørn. The reaction to this event came later, when I fully realised the

enormous debt I owed him – a debt that I would never be able to repay. That he saved my life by sacrificing his own is indisputable.

In the summer of 1945 I visited his parents and it gave me great satisfaction to tell them that Bjørn had occupied an important position in Trondheim and that he had not given his life in vain. They were magnificent people who were visibly reassured on hearing that Bjørn had played such a major part in the Resistance.

The last respects that Knut and I could pay to Bjørn was in the Autumn of 1945 after his body had been found. At a small memorial service in the Maria Chappel, Knut and I acted as honour guards.

Kristian’s days as an SIS radio operator in Norway were over. On Sunday February 7th he arrived in Stockholm and three days later he was back in London.

After all the ‘welcome home’ parties the dull, everyday life began. Kristian had only one wish – to get sent back to Norway. He tried every channel, used every contact – to no avail. Until the end of the war he continued to pester for a posting to Norway but he remained ‘chained to a desk’ in Whitehall. His experiences there, his comments and his reflections on life in London are interesting and controversial but they belong in another section of this website.

Kristian Fougner’s war merits:

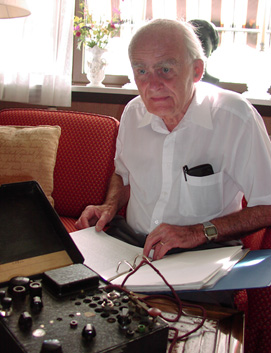

Kristian Fougner with his ‘Polish’ radio in 2010

(Photo: Magne Lein)

Distinguished Service Cross (UK)

War Cross with Sword (Norway)

Kristan Fougner’s comments on same:

The fact that I was awarded first the DSC and later the War Cross made things even worse. I hadn’t done anything to deserve such honours. On top of everything I was weak enough and vain enough to accept these medals.And he quotes:

Those who have enjoyed much undeserved honour, must later accept much deserved humiliation. (Bj.Bjørnson)

The military leadership, however, thought otherwise:

War Cross Citation:

… In 1943 Lt. Kristian Fougner served with the Intelligence Section. He also worked for the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Fougner had been involved in secret resistance in Norway since Autumn 1940 and went to Great Britain in April 1942. Already in May the same year he was sent back to Norway on a mission in Trøndelag. Fougner established a radio station which was operated with great success. A further radio was sent over and Fougner found men as operators. Arrests by the Gestapo made it necessary for Fougner to return to England but he had to return to Trondelag again because of technical difficulties with the senders. Once these were fixed Fougner returned to England December 1943.

Fougner’s Diploma carries the following addition: For special service contribution in connection with secret military operations.)

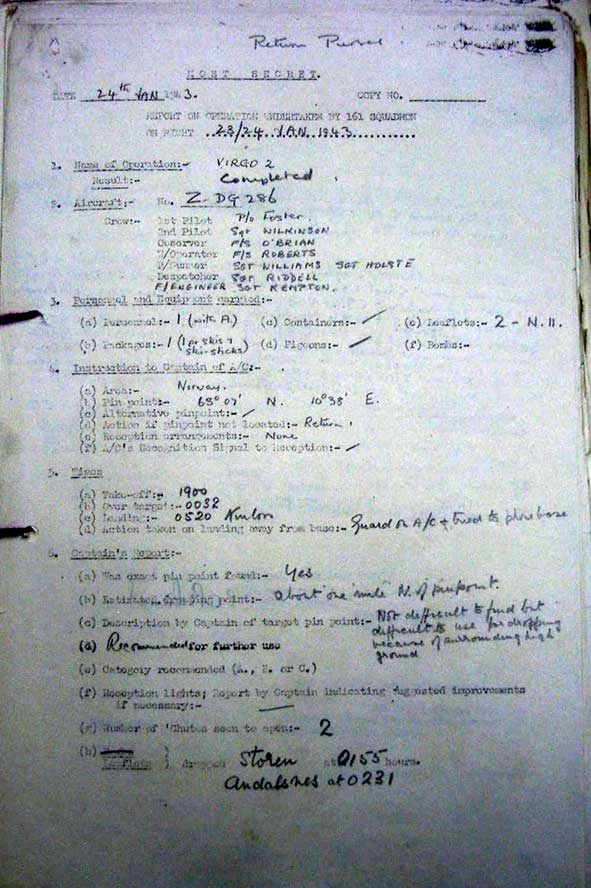

The following is a copy of the first page of the report given by the pilot of the aircraft that carried Kristian to Norway in January 1943. Note the ‘packages’ comprised “1 pr skis & ski sticks” and the comment: “not difficult to find but difficult to use for dropping because of surrounding high ground.”

1 Except those owned by NS members.

2 A secret intelligence organisation

3 In his official report, Rørholt used the word Nursemaid.

4 See also, Naval Matters

5 P9 – The ‘Norwegian’ section within SIS London

6 Johanna was later murdered in a German concentration camp.

7 See ‘ -og tok de enn vårt liv’. by Per Hansson.

8 See The Tempsford Taxis