Many of those who were actively engaged in resistance against the German occupation of Norway, have been hesitant to talk about their experiences. Often their families have had to be content with small episodes that only whetted their appetites for the full story.

Many of those who were actively engaged in resistance against the German occupation of Norway, have been hesitant to talk about their experiences. Often their families have had to be content with small episodes that only whetted their appetites for the full story.

Eva is the matriarch of one such family and they gave their full support when we suggested that she tell us her story.

We noticed that Eva was limping when we arrived for the interview. She explained that it was nothing – just a reminder of a summer day when she scraped her leg jumping from a boat onto land – as though hopping around was quite normal for an 87 year old!

Growing up

Eva 1918

Eva was born in Mosjøen in 1918, the second of three daughters in a close-knit and respected family. They moved to Glomfjord, N. Norway in 1920 where her father, an army captain, became auditor for the Glomfjord foundry.

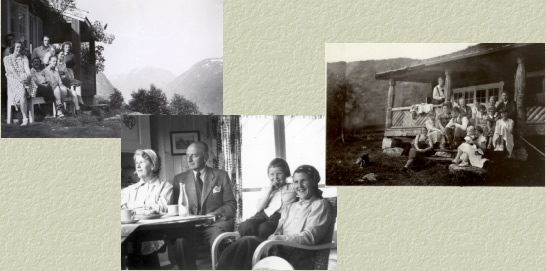

Else, Eva, Vaar, mother, and grandmother

He died of cancer when Eva was 7 years old. Her mother remarried in 1931 and the girls got a loving father who later financed their education and travel around Norway. “When we children talked about the marriage to friends we always said that father married us!”, says Eva.

Eva’s artistic mother painted, wove, embroidered and learned brocade painting in 1925 while she was in Oslo during her husband’s illness. She was also practical and held the important position of chief telegraph operator for the district. Eva and her two sisters Else and Vaar, often ’helped’ their mother at the telegraph station – a pastime that later proved useful for Else in a critical wartime episode.

Glomfjord

Glomfjord, situated at the head of a fjord north of the Arctic Circle, had no land connection to the hinterland at that time. Bodø, the nearest large town, was 26 hours away by Coastal Steamer; now the 150 kilometres can be covered in just over 2 hours by road. The history of Glomfjord is the history of Norway’s development of hydro-electricity; the task of harnessing the 442 metre high waterfall started in 1918. In 1927 the production of Aluminium started and because both the raw materials Glomfjord and finished products had to be shipped in and out, Glomfjord became the busiest port in Northern Norway.

Skiing 1910

Life at home was cultured and serene but nature outside was raw and brutal. The three sisters learned to ski early and thought nothing of plodding slowly up a nearby mountain for three or four hours only to swish down again in 15 minutes: “we were fantastic skiers and we loved the mountains” remembers Eva who said that one of the mountain passes, was named after her first father (Granskaret).

Eva at her confirmation

They were also enthusiastic members of the Girl Guides. Eva became a troop leader and her most memorable experience was leading a group of 19 girls from Glomfjord to an international Guide camp at Mandal in southern Norway. They travelled by Coastal Steamer, bus and train to Mandal but on the way back they got a lift on a freight boat all the way from Mandal to Glomfjord.

Although pre-war Glomfjord was physically isolated, the inhabitants kept abreast of current events by radio. Even so, Eva commented that compared to today’s media flood of information, their limited sources provided little knowledge of the political realities in Germany and the rest of Europe.

It was soon obvious to everybody that Eva was destined to become a children’s nurse because from an early age she was always lifting and carrying young children and babies. As she grew up Eva became a familiar figure as a helping hand with children around the town. In 1936 the need for professional training called her to Oslo where she enrolled at a Domestic Science College. In those days one had to know how to be a housewife before beginning to train as a children’s nurse. She qualified in 1938 and remembers:

“I loved my job as a children’s nurse, I can think of nothing better than caring for new-born babies. At that time, some young mothers hired nurses to help them during the first few weeks after they came home from hospital. I spent many happy hours in some of the best houses in Oslo. I learned a great deal”.

The Invasion

Eva was living with her two sisters at Besserud, Homenkollen, in an apartment with a splendid view over Oslo and the Oslofjord. On April 8th 1940 the sisters went to bed at their usual time but the first air raid siren woke them up at 0015. The electricity was cut off shortly afterwards. The second alarm sounded at 0430, accompanying the drone of German aircraft approaching Fornebu airport. The sisters saw the aircraft from their window and they telephoned the local newspaper ‘Aftenposten’ to find out what was happening. The reply was a terse: “This is the real thing”.

The German invasion of Norway, the sinking of the Blücher and the delayed occupation of Oslo are separate stories. For the Gran sisters, with their background in girl-guide leadership and nursing, the escape of the Government and Royal Family and the military resistance, put them in the front line. On the evening of April 9 Else, as leader of the Girl Scouts Association in Oslo, was ordered to a Red Cross emergency post near Fagerborg church. Else, her two sisters and several others volunteers served refreshments and dispensed comforting words to visitors who were both afraid and confused. The worst experience was when a convoy of vehicles thundered by on its way to a local crematorium with a gruesome cargo of German corpses from the battleship Blucher.

Next day, April 10, the so called “panic day” because of rumours that Oslo would be bombed precisely at noon, thousands of people left their homes and fled to the countryside. Eva and her sisters had an uncle who lived in a house at Vettakollen. On ‘panic day’ he opened his home for the needy and got his three nieces to assist him. On the way there they met scared children, women, and whole families whom they took with them to the warmth and safety of their uncle’s house. He had a friend who owned a large business in Oslo and Eva told us; “Uncle Anton went into town with a van and came back with heaps of good food – sausages, bread and butter. We put together a meal so that the, by now, large numbers of involuntary guests didn’t have to sleep on empty stomachs.Next morning the bomb scare was over, the overnight guests left and we could get the house ship-shape again”.

In Action

On April 12 Eva and her two sisters answered a call for assistance and reported to the Red Cross Hospital with knapsacks on their backs and skis over their shoulders. They were given Red Cross armbands and the necessary papers and ordered to report to the small village of Hov, about 120 kilometers from Oslo. The Germans had not yet blocked the roads so on the first leg of their journey they enjoyed the comfort of a Mercedes. At Guriby in Lommedalen however they had put on their skis – destination Sundvollen, a steep climb in snow that was already beginning to melt in the spring sunshine. Worse than the rotten snow were the German aircraft that strafed them, probably thinking they were Norwegian troops. They spent anxious moments diving into the snow and finding safety under trees. At Sundvollen, they met a Dr. Fürst from Oslo who drove them to Hønefoss, eerily quiet and deserted after the evacuation. “The shops were opened for us so that we could obtain food, medical supplies, and other necessities” said Eva. Then they continued, along country roads with sounds of battle on both sides, with the occasional stop and dive in ditches in fear of low flying aircraft, to their final destination, Hov and the nearby Søndre Land Hospital. Dr. Holmsen, the head doctor reminded them that according to the Geneva Convention, all combatants, both friend and foe, must be given the necessary medical assistance.Their task was to establish a clinic for soldiers of both nations in the empty community hall.

Conditions were not good. Patients had to be laid on the floor. The villagers had fled from their homes and farms, electricity and water lines were cut. Luckily the owners of the neighbour farm, Sarastuen, had decided to remain. These kind people provided the clinic with vegetables, whatever other food they had available and wood for the clinic’s stove. Medical supplies were meagre and much of the equipment had to be put together from emergency kits by the ‘personnel’. ‘Personnel’ comprised a young local girl, two young men – ‘jacks of all trades’, the Red Cross leader, a young female medical student and the three Gran sisters. The daily routine was more than enough to keep everyone busy.

There were other challenges. One day they were given a calf for food. Who was to butcher it? “You have been to the school for housewives” Eva was told; “you do it.” She was practically in tears because she had only a pocket- knife and had absolutely no idea how to start. Finally the farmer’s wife took over the job. Fresh meat was a welcome addition to the menu for the next few days. The less seriously wounded patients were happy to help with the small household chores like peeling potatoes, washing up and cleaning the stove.

As the weeks progressed, the fighting around them intensified and the number of wounded increased steadily. After one hard-fought battle a group of 30 badly wounded showed up – accompanied by a German doctor who tirelessly treated patients of both nationalities. But many died and the nurses attended the funeral services. Eva’s voice broke and tears welled into her eyes as she remembered these sad gatherings, the terrible wounds, the pitiful conditions and the sheer waste human life.

Assisting soldiers from both armies was especially poignant – but it had its lighter side. One slightly wounded German soldier was laid on a bed without mattress or pillow. Eva told us that as she bent over him she thought he said, “Give me a kiss.” “I was so annoyed that I slapped him across the face and then felt terrible when a another patient told me that the soldier had only asked for pillow.” (Kyss = Norwegian for kiss, Kissen = German for pillow). Another time, when one patient complained about a German soldier being taken care of, another Norwegian soldier shouted: “He is just as good as I am.”

Gradually the Germans gained the upper hand in the battles against the ill-equipped Norwegian forces. The telegraph station had been abandoned and Else, with the experience at her mother’s knee, so to speak, operated the equipment and relayed messages, many of which were in code. The doctor in charge of the hospital had warned them to leave immediately the Germans arrived. One day Else was working in the telegraph office when she heard the rumble of German vehicles. She rushed outside and tried to look inconspicuous. When a couple of German soldiers came up to the station she pretended she was just a casual passer-by. A few days later she fell off her bicycle and spent the next three months in hospital herself.

By Foot from Oslo

Leaving Else in hospital, Eva and Vår left Hov after six exhausting and challenging weeks. On their return to Oslo they were penniless, jobless and had had no contact with their family in Glomfjord for almost two months. They found Oslo still in a state of uncertainty. The Germans were trying to keep the population passive but the prevailing mood was ominous and resistance was increasing. On May 31 the girls decided to go home – just like that. In sports clothes, stout shoes and wearing their Red-Cross armbands, they took a tram to the outskirts of the city and began to walk up the road to Trondheim.

Keeping a careful eye out for German military vehicles they managed to hitch a few rides and on the evening of the first day they walked over the bridge at Minnesund. At Hamar they approached the driver of the train and told him their story. “Jump in” he said, and they emerged safely at Lillehammer. “We walked, and walked and walked – do you realize how far it is from one end of the Gudbrandsdal valley to the other?” asked Eva and continued:

“We felt safe in flagging down a post office van – but it was driven by a German soldier. He didn’t seem to think there was anything strange in two young women hitching a ride in the middle of nowhere. He was so busy trying to talk to us that he didn’t see the car turning out of a side road – and certainly didn’t stop when the car clipped the rear end of our van.

We hid and slept in gardens or under trees, washed in the river, begged food from farms and shops – you’ve no idea how good cold porridge with sugar tastes when you’re really hungry. We rode in a hearse but the driver assured us there was no body. We were even happy one day to sit in a horse-drawn cart. On the Dovre mountain plateau we came across a band of Norwegian war-prisoners working on the roadside. They said we were safe with them – there was only one German guard and he was reassured by our Red-Cross armbands. We sat in their trucks and drove with them to their camp at Hjerkinn. Then we took the spectacular mountain path down Gauldalen.

Two men in a car stopped and gave us a lift on the outskirts of Trondheim. From the way they spoke about the political situation we realized that they were Norwegian Nazi sympathisers – not very nice men at all. Vaar began to moan and say that she was not feeling well and was about to be sick. Fearing for the interior of his new car the driver stopped, we jumped out – and ran as fast as we could – not even thanking them for the lift. After a few minutes we were in the streets of Trondheim that we knew so well.”

Eva and Vaar had visited their aunt in Trondheim many times before but never had they arrived so unexpectedly. The aunt, uncle and two cousins welcomed them warmly and listened almost open mouthed as the girls related their recent experiences. The girls were told that there was no chance of them continuing their journey because the fighting had intensified and the grip of the invader had become firmer – they were welcome to stay as long as they wished.

But Eva and Vaar were determined to continue and next morning at 5 they left silently and started walking again. Their interim destination: Eva’s godmother who lived in Mosjøen – some 450 kilometres north of Trondheim.

Tired, weary, and bedraggled after several days’ toil they finally reached Mosjøen. Eva’s Godmother was married to the local doctor so they were in good hands. A fisherman offered to take them along the coast to Glomfjord but the girls, afraid of mines and bombs, refused:

“I don’t know why. After all the dangers we had faced you wouldn’t think a sea journey would scare us – but somehow it did” said Eva. So the doctor drove them to Hatfjelldal where they hitched a ride on a railroad maintenance locomotive to Mo I Rana.

Eva continued her story:

“Uncle Anton lived in Mo i Rana and we stayed with him to plan the last leg of our journey. The main road was impassable because of the fighting so he got someone to row us across Langvatn and we continued on a trail that led alongside the fjord and then up towards the mountains. In the meantime the fishing boat from Mosjøen had reached Glomfjord and our parents were told that we were on our way home by way of the mountain pass from Mo i Rana. When Uncle Anton arrived back in Mo, he found that a fisherman named Simon had been sent by our parents to look for us because a German plane had made an emergency landing right in the middle of our planned route. Simon crossed the fjord again in his fishing smack, cruised parallel to the shore looking for us and went ashore when he reached the innermost farm. When we got there, and heard the greetings from our parents we both broke down and cried. When we continued our journey it was still light. The midnight sun had disappeared behind a bank of clouds and a gale force wind drove the snow straight into our eyes. The mountain snow was melting we were wading up to our hips in slushy snow, and would never have survived without Simon’s help.”

At one point, a roaring waterfall-fed river blocked their way. A thick, tree trunk spanned the river as the only way across. The surface was soaking wet, slippery and buffeted by hissing spray. Simon showed them how to cross, sitting on the trunk, and hitching forward keeping both hands firmly gripped in front. Eva went after Simon. Then Vaar, but she was so afraid that Simon had to go back to her and they crossed together with her holding onto his back. The river was their final obstacle. Shortly afterwards they arrived at Melfjordbotn, Simon’s home, where his parents took care of them with food and comfy beds for the night.

The next day, June 17th, in Simon’s motorboat, they arrived in Glomfjord and went ashore wearing the only dry clothes they had – their nightdresses. They were welcomed by a crowd of people, including a weeping but happy mother and father. They had travelled about 1500 kilometers in 17 days and counted 17 different means of transportation.

“We didn’t have a day’s sickness and our only ‘injury’ was sore feet” was Eva’s summing up.

Vaar and Eva 1941

Back in Oslo

In January 1941 Eva returned to Oslo to continue her work as a children’s nurse and to be with her sister Else who was studying pottery. In Oslo, conditions were much worse than before; increasing restrictions, shortage of food and even more uncertainty concerning the nature of the occupation. After a few months the whole family moved to Hoyanger where they lived for two years. By 1942 Eva was leader of the “Sanitetsforeningen”s kindergarten in Hoyanger but she moved back to Oslo in January 1943 to attend the Barnevernsakademiet. In Oslo she moved into the apartment of “Aunt Hanna”, a prominent library director, and friend of the family. Eva was welcomed to her new home with the warning: “In this house we ask no questions and tell no tales.” Finding weapons under a sofa and a refugee Jew in the cellar, Eva quickly understood the seriousness of this admonition – and was soon involved in illegal activities herself. (She was also appointed “boss” of the air-raid shelter in the basement with the thankless task of ringing the doorbells of all the apartments whenever the air raid warning sounded.)

Her job was simple but dangerous. One day each week she was to go to the main library and pick up a package she would find on the counter. If there was no package she should just look at some books and then leave. The packages contained about 30 illegal newspapers and Eva delivered these to a list of local addresses. The German occupiers realised that these newspapers were an important source of moral support for the Norwegian population because they countered the one-sided news presented in the Nazi-controlled press. Anyone caught distributing illegal newspapers was imprisoned, interrogated, often tortured and sometimes executed. Luckily, Eva was never apprehended.

At the Barnevernsakademiet she found many friends who sympathised with her own anti-Nazi feelings. By this time the resistance movement had developed into an organised but disparate force that operated throughout the country.

In February 1943, nine intrepid Norwegian soldiers, under incredibly difficult conditions, blew up part of the Norwegian Hydro plant at Rjukan in southern Norway. Rjukan was German’s only source of “heavy water”, a vital ingredient in the production of an atomic bomb. This, and later sabotage actions against the production and shipping of heavy water”, resulted in the German failure to make the feared, nuclear “ultimate weapon” in time to change the course of the war.

The men who accomplished the Rjukan raid became popularly famous as “The Heroes of Telemark”. In the forests and hills around Oslo there were other “unsung heroes”; resistance soldiers who reported to London, who carried out sabotage and who laid plans for a possible uprising whenever the opportunity occurred. These men, in turn, were dependent on others to help them with food and supplies and this was where Eva and her friends at the Barnevernsakademiet came in. At weekends they would visit a bakery in Majorstuen, collect bread and other food in their rucksacks, take the tram to Frogneseteren, strap on their skis and literally “head for the hills” with their important cargoes. The “Boys in the Woods” (“Gutta på skauen” was the popular Norwegian expression for the resistance fighters at the time,) met their suppliers at pre-arranged spots deep in the woods where both food and information were eagerly exchanged.

We asked Eva for her thoughts about the way people reacted to the occupation:

“It seems to me that while obviously there were some who supported the invaders, most people were against them. In both camps there were degrees of commitment but I think that in a thousand different ways the majority of the Norwegian population hated the occupation. The feeling among my friends was a furious anger with the Germans who had no business being here – they had to get out. We discussed politics before the war and already then people had begun to take sides – pro England or pro German. Most of my friends were Anglophiles and I was all set to go to England as an “au pair” just days before the outbreak of the war in 1939. I remember that many Norwegians were pacifists before the war but most of them changed their stripes quickly after April 9th.

I hadn’t met any Germans before the war except for a lady who was married to a Norwegian engineer at the Glomfjord plant. She had lots of friends but the war ruined everything for her – she isolated herself from her friends so as not to compromise them.

My own grandmother studied music in Germany and my stepfather studied in Dresden – at a time when it was difficult to study either music or engineering in Norway. The worst thing about 1939 and early 1940 was the uncertainty – many people just didn’t know which side to support.”

In July 1944, as part of her training, Eva was working at a camp where children, from 2 to 5 years old were being cared for because of the lack of food and difficult conditions in Oslo.

One day, as Eva and another student were feeding the children, two German soldiers burst in. One of them shouted: “Fräulein Gran, Fräulein Gran”. When Eva identified herself the soldier said that she was under arrest and that she must come with them immediately. She protested that she couldn’t leave the children; they had to be fed and then changed. She remembers now that she was angry and also afraid – her father was, after all, in hiding, her sister Vaar was “somewhere in Valdres” and she thought of her own weekend food missions. Still she was adamant about not leaving the children until they were ready for bed. She was both surprised and relieved when the soldiers relented somewhat and showed that they were fond of children.

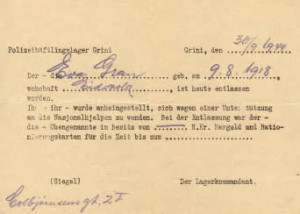

Imprisoned

The soldiers drove Eva to Victoria Terrace – the forbidding and infamous headquarters of the Gestapo in the centre of Oslo. She was placed in a cell together with several men and women and as soon as the guards left, one of the inmates looked around slowly at each of the others and said to Eva; “The rule here is that we do not talk – not even to each other.” From this Eva understood that one of the “prisoners” could be a “stool pigeon”. Shortly afterwards she was taken in for questioning but she was the one who asked first; “Why have I been arrested?” “You know very well” was the reply. This exchange became the refrain that was repeated at the beginning of all future interrogations.

I kept asking why I had been arrested and saying that I was innocent. They kept asking me whom I had been helping and where we had been meeting. She was shown a photograph of a man whom, luckily, she did not know. “What was the family name of your mother?” was the next question and Eva answered almost without thinking: “Lund.” She realised almost immediately that this was wrong – her grandmother was a Lund but her mother had been born Devold – and unbeknownst to Eva, Devold was the name of the man in the photograph. Again, luckily, she decided not to correct her mistake so as not to appear confused and disoriented. Later, at Grini, Eva learned the reason for this questioning when she met several members of the Devold family. The man in the photograph was one of the ‘men in the woods’ whom Eva had probably met during her food delivery trips. In the spring of 1944 he had been shot and killed during the Flaskebekk action. In his pocket the Germans found a scrap of paper with one word written on it – “Gran.”

Eva remembered the following weeks vividly: “All interrogations took place at Victoria Terrace. We were transported to and from in open-backed trucks fitted with individual cages. My first trip was on July 1. Next day I was taken from Grini to the prison at Møllergata 19 in the centre of Oslo. Here I was forced to sit on a high, hard, straight-backed chair in the corridor. A huge Alsatian dog sat a few feet away and since I had a natural aversion to dogs I was terrified and dared not move. After a while they drove me over to Victoria Terrace again.”

“Two slices of bread, and nothing to drink was all we were given to last the day during these interrogations. I went through 15 such days. I was not physically tortured but was constantly humiliated – like the time I had to go to the toilet. An armed escort followed me all the way and stood in front of the open door haranguing me with a long praise of Hitler and the future of Europe when the German armies were victorious – and this was a Norwegian. I was furious – and helpless. Four men were present at the first interrogation and every time they urged me to confess one of them held a lighted cigarette close to my arm, but not close enough to burn. At the following sessions I was questioned only by the ‘boss’ and his assistant.”

In between interrogations at Victoria Terrace Eva was interred at Grini, the equally notorious concentration camp situated on the outskirts of Oslo. The Germans had taken over Grini shortly after the invasion in 1940 for political prisoners. Originally designed for 700, the camp at one stage housed 5400 men and women. Some of these were already well-known professors, scientists, writers, politicians and artists; Francis Bull, Einar Gerhardsen, Johan Borgen, and Arnulf Øverland for example. Others became famous after the war, notably the Nobel Prize for Chemistry recipient in 1969, Odd Hassel. By the end of the war more than 19,000 prisoners passed through the gates of Grini.Many of these were deported to concentration camps in German and never returned to Norway.

Eva remembers Grini:

“Two German female attendants were in charge of the women’s section. One if them we called ‘Grandma’ and she was OK – the other was a she-devil. We were registered with typical German thoroughness, repeating the same personal information; name, date of birth, where born, etc., etc., that I was to repeat hundreds of times during the next three months. Our “home” was a large room with bunks, seven high, on either side. Mine was the lowest – with a worm’s eye view of the cockroaches that infested the floor and walls. Again we were given the warning not to talk until we had got to know the routines and other inmates. I met many interesting fellow-prisoners, from all walks of life, from all parts of the country and from all occupations and professions. Most of them were older than I. They watched over the younger inmates and organised services on Sundays.”

“One day, several unhappy young girls from Stavanger arrived at the camp, sent because they had been ’associating’ with Germans. Scarcely educated and from poor homes, they had no idea of any wrong doing and could not understand why they had been ‘exiled’ to Oslo. We welcomed them, treated them fairly, and made them feel at home and soon they were chattering and laughing like any other teenagers”.

“Otherwise, one day was very much like another. The male prisoners were responsible for the food which was in short supply; bread, thin soup, thinner coffee and occasionally goat cheese. Once in a while they managed to smuggle in herring and potatoes wrapped in newspaper. We had to eat with our fingers – all utensils were handed down or improvised. We women spent our time cutting up all kinds of material that could be used for making trousers for the men.

The Gestapo must have decided that I really did not have any connection with a spy or resistance ring because my regular trip to Victoria Terrace stopped after about a month. Then I was moved into a hut with six other women. Those who had been there longest received packages from the Red Cross which were shared with all of us. We spent at least two hours each day lined up on the parade ground for inspection and counting so the days passed relatively quickly.The worst memory I have is of September 20. We were hustled out of bed in the middle of the night and lined up outside in the usual manner. It was cold and we stood there for two hours while German officers called out and separated a large number of inmates, including two from my hut. Later we learned that they were to be sent to concentration camps in Germany, fortunately my room-mates came back after the war. It was terrible – especially to see the younger ones been chosen – some of them were only boys.”

And for the second time, Eva’s voice wavered as she brushed away tears from her eyes and was unable to relate many of the other gruesome episodes she had experienced at Grini.

When Eva realised that she was no longer suspected of illegal activities she began agitating for her freedom so she could return to her studies. With the help of co-prisoners she wrote a letter to the commandant explaining that it was important for her to take part in the forthcoming examinations. A few days later she was informed that she was to be transferred to Bredtvedt a prison located on the other side of Oslo. After heartfelt farewells and many verbal messages promised to be delivered, she was set free. With her personal possessions in a cardboard soap box she was driven away in the familiar cage on the back of a truck. The truck stopped after only a short drive, the driver unlocked the cage, handed Eva a green sheet of paper and ordered, “out.” A confused Eva could read the German “Frei” on the paper but suspecting some trick she cried “No, no, I’m to go to Bretvedt.” The driver simply drove away. Eva stood there, close to the centre of Oslo, her meagre belongings on the ground and a look of wonder on her face. Then, amazingly, in one of the small coincidences that help to make life sparkle, her Aunt Hanna strolled around a corner and practically bumped into her. Arm in arm they walked to the apartment at Observatorie Terrasse 6

Eva’s rooms had been ransacked –almost certainly by the Gestapo in the search for evidence of her ‘spying’. In spite of the deliberate destruction and disarray in the apartment, nothing of value had been taken – and kr. 200 in cash remained untouched in a drawer.

Eva’s rooms had been ransacked –almost certainly by the Gestapo in the search for evidence of her ‘spying’. In spite of the deliberate destruction and disarray in the apartment, nothing of value had been taken – and kr. 200 in cash remained untouched in a drawer.

After her involuntary absence from school, Eva had a lot of catching up to do. She spent the remaining months of the war studying, visiting her parents who were in hiding near Kragerø, and taking exams. She became engaged and started a new life in a Norway at peace.

Post-war Years

After settling into a new house, and with her two children out of the infant stage, Eva felt the urge to pick up the threads of her professional life – caring for children – and to developing the skills learned at the Child Psychiatry course she had taken in 1943 and 1945. First she became a pre-school teacher at a local kindergarten and then, in a similar capacity at Rikshospitalet. (The National Hospital).

The National Hospital, founded in 1811, was originally a facility for the study of medicine and the treatment of patients who lived outside Oslo. At the end of the 19th century several new, specialized departments were established but a separate clinic for Psychiatry was built at Vinderen, not too far from the hospital. During the years after the war, however, it became obvious that the National Hospital needed its own psychiatric expertise and a new Psychiatric Department for Children was created in 1951. The new department had to be satisfied with a basement location under the leadership of Dr. Hjalmar Wergeland who had returned from Sweden for the new position.

In the children’s ward upstairs, Eva’s patients came from all over Norway, with various illnesses that sometimes kept them in hospital for anything up to six months. Looking after and teaching these children was the kind of work that Eva knew, loved, and was good at. In 1954 she was asked, not surprisingly, if she would consider taking a temporary position in the comparatively new Psychiatric Department and not surprisingly, she said “yes.”

In the Psychiatric Department Eva found that the children completely different from the ones she was used to: autistic children, children with anti-social tendencies, hyper-active children and children with nameless problems that had scarcely been recognised and certainly not studied in depth. The challenge was first to learn how to understand the problems and then to help the children find a better way of living with them. The work could be dangerous as well as challenging – Eva remembers being almost struck by a flying knife; “but the team-work was fantastic, doctors, teachers, parents and specialists working as one.”

When Dr. Wergeland needed a permanent pedagogue to replace Eva’s ‘temporary’ position, Eva applied and got the job. Psychiatry, especially child psychiatry, was still in its infancy in Norway and the only specialists were in Oslo. As a result, Eva and her colleagues began a hectic travel programme, spreading information, teaching and advising at hospitals and clinics throughout Norway – and agitating for the establishment of new psychiatric clinics.. This, in turn, entailed much study and research on their part as most of the advances in the discipline came from abroad; from England, the United States and France. One of the first new approaches that Eva embraced was to look beyond the child’s disability and concentrate on its innate, healthy abilities.

In 1955 the organization ‘Save the Children’ in Sweden gave the department a generous gift: a home for the treatment of children with psychiatric problems. ‘Lille-Sogn’ as the home was called, became a welcome addition in the struggle to combat children’s psychiatric problems. The gap in the system was recognition and treatment of the problems in older children and youths. Not until the sixties did the authorities first begin to address this problem. In 1963 the first stage of the government’s plan, a psychiatric clinic for young people, opened at Sogn, a close neighbour to ‘Lille-Sogn’. In 1968 the department at the National Hospital was merged with the clinic at Sogn and renamed ‘The Childrens Psychiatric Department, Oslo University. Thus the Government’s plan for a centralized psychiatric facility was realized and became the ‘Statens senter for barne-og undomspsykiatri,’ (SSBU). Eva became head of the children’s department.

Throughout these changes Eva and her colleagues maintained busy schedules travelling around Norway visiting homes and schools of children who had been patients at the clinic.

“After a while, the facility became a fully-fledged polyclinic, with psychiatrists, psychologists, teachers, pre-school teachers, qualified welfare workers, and psychiatric nurses who were often in training with us.” explained Eva.

In addition, since the clinic was University accredited, the task of lecturing to student doctors was also partly hers. Neither had she neglected her own training and development.

In 1953, a pioneer of modern psychiatry, Dr Nic Waal, had founded an institute for psychiatric treatment of children and young people and the improvement of such treatment through research, development, and teaching. For two years, combined with a full time job and family, Eva studied at the institute, soaking up new ideas and discovering new challenges. “What I learned at Nic Waal’s Institute was phenomenal”, she told us, and continued; “we could discuss and analyze actual cases from the clinic and then get specialized tuition that related to the case.”

Looking back, the thing Eva remembers with most satisfaction is the ‘play seminars’ that she developed for adults of all disciplines who were involved in child/youth psychiatry. Basically the problem was that nobody knew how to motivate and interest 40 or so children from various wards. “My idea was to think of the games and pastimes we all had played as children and recall what we remember of them, both positive and negative”, said Eva. “Only adults attended these seminars which occupied 3 hours, one day a week for four weeks – a total of 12 hours. After each segment the participants returned to their wards, continued the games with their children, and reported back to me with their experiences.” Soon the seminars became well known and Eva was once more travelling to different parts of the country to conduct her ‘play seminars’ in clinics, hospitals, and homes.

A side effect of this was, as Eva’s daughter said; “her own children always had the most enjoyable birthday parties” – proof enough of Eva’s effervescent, playful spirit.This period wasn’t exactly a party for Eva. In 1965 her husband, who had been intermittently ill for several years, died after a tragic ski accident in the hills above Oslo. Eva immersed herself in her work but continued, with her children, to enjoy summer holidays sailing from their cabin by the fjord and winter skiing that had always been an important part of their lives.

A side effect of this was, as Eva’s daughter said; “her own children always had the most enjoyable birthday parties” – proof enough of Eva’s effervescent, playful spirit.This period wasn’t exactly a party for Eva. In 1965 her husband, who had been intermittently ill for several years, died after a tragic ski accident in the hills above Oslo. Eva immersed herself in her work but continued, with her children, to enjoy summer holidays sailing from their cabin by the fjord and winter skiing that had always been an important part of their lives.

In 1968 she moved with her two children to an apartment close by the clinic at Sogn where; “We had Nordmarka on our doorstep and were able to enjoy the fresh, open air. Holidays were more modest than they are these days and we worked six days a week until 1972.

In 1968 she moved with her two children to an apartment close by the clinic at Sogn where; “We had Nordmarka on our doorstep and were able to enjoy the fresh, open air. Holidays were more modest than they are these days and we worked six days a week until 1972.

At work, life was more hectic than ever. The demand for psychiatric treatment and information about related illnesses increased dramatically. Through the ‘Play Seminars’ it was shown that many afflicted children could partially manage their problems, or at least accept them – and the support of siblings was often decisive. As Eva’s lectures became more popular her leisure time diminished because most of the engagements were in the evenings or at weekends. Eva says: “I enjoyed my work and felt that my experience could benefit others. I held several seminars for teachers and health personnel: ‘Children in hospital’, ‘Children and fear’ and ‘Children and games’ In spite of the demanding workload, Eva herself remained fit – she claims that she is practically immune to all illnesses.

When Eva started her career in the early 60’s, there were 21 hospitals and clinics for psychiatic patients. When she retired, more than 20 years later the number had risen to 37 and 22 of these were for children and young people. She is satisfied with the development. From being a centralized institution the children’s psychiatric clinic became more locally attuned. In her later years Eva was heavily involved in polyclinic assistance to kindergartens, schools, and families.” Working with the polyclinic was enjoyable and I owe a greatt debt to my colleagues for their help, support, and friendliness throughout the years.”

Just before her retirement, at 67, Eva moved to a cosy retirement apartment at Nordstrand, close to where her children and grandchildren live. Summing up, Eva is satisfied:

Else and Geoff Ward

Asker, Sept. 13, 2006