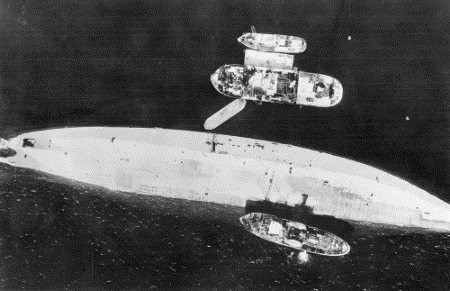

On the night of April 8th 1940, the people of Trondheim went to bed as citizens of a peaceful city in an independent land. When they awoke next morning, the heavy cruiser “Hipper”, and four destroyers were anchored in the harbour and seventeen hundred German troops occupied the city. For the Germans, Trondheim, (pop. 65,000) was an important strategic port, a ‘gateway’ to Northern Norway and a safe haven for ships preparing to attack allied convoys heading for Murmansk. The unwillingness of the British military leaders to land and maintain troops in an attempt to eject the enemy, and the inability of the Home Fleet to stem the flow of German troops had dire consequences – and some unexpected benefits. German control of the ports and airfields was a constant threat to Allied supply routes but the very nature of this control tied up essential resources that the Germans had greater need for elsewhere.

Trondheim Harbour

The Hipper had been the first German ship to encounter a unit of the British Home Fleet when, almost accidentally, she sighted the destroyer Glowworm which had been separated from the fleet in search of a man overboard. The Hipper quickly silenced the smaller vessel but the Glowworm in a final death throe, managed to ram and damage her. A month later, on June 9 the battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau entered the harbour. The Scharnhorst had been severely damaged by a torpedo after sinking the British aircraft carrier Glorious and her two supporting destroyers. A young girl in Trondheim wrote in her diary, “We can see the Scharnhorst clearly from the veranda. It is the one with the hole in it. An English submarine has done it. The hole goes all the way through the bow… a motorboat could go through it.”[1] This may have been an exaggeration but regardless, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau left Trondheim at the end of June for extensive repairs at Wilhelmshavn. They did not return to active service until January 1941 – when, again, they headed north.

Local Resistance

Many Norwegians were firmly convinced that the allies would repeat their attempt to establish a bridgehead in Norway. According to Reidar Jørgensen, a noted Norwegian Olympic athlete and teacher in Trondheim, “…several men in Trondheim had started to build up a Resistance movement after the capitulation of the Norwegian Forces.” Jørgensen had direct contact with four who were particularly active: “Good friend and neighbour Valdemar Aune, good friend and fellow-athlete Professor Leif Tronstad, subsequent Prime Minister John Lyng and an old-friend and fellow athlete Olaf Helseth.” [2]

All these men were to play decisive roles in the Resistance movement. After April 9th, Reidar Jørgensen travelled to Lillehammer to enlist but, like many others throughout Norway, he was turned away. He joined forces with a group that had established a radio station in direct contact with GHQ. They relayed messages, collected information. Their orders were to keep up their activities for as long as possible. They continued to work alongside the allied troops in Gudbrandsdalen and made their final transmission at Dombas. On his return to Trondheim, Jørgensen helped Lyng with the printing and distribution of illegal newspapers and continued his resistance work. He was a member of the ‘Monday Club’, with, among others, Just Finne, Professor Vogt, and Henry Gleditsch[3], a gathering of ‘Good’ Norwegians[4] that met regularly to discuss and give advice, on illegal activities and other aspects of the occupation.

Special Intelligence Service (SIS)

The latter part of 1940 and the first half of 1941 were difficult months for the Norwegian presence in London. Norwegian men and women, who arrived in increasing numbers, all wanted to “do their bit” for the war effort and cried out for action. At the same time, misunderstandings between the exiled Norwegian government in London, the growing resistance organizations in Oslo, and the British military authorities, created uncertainties, mistrust and inaction.

The British were desperate for information about the situation in Norway and especially about ship and troop movements. Radio contact with England was essential if this information was to be of any use. The first two radio stations, “Hardware” in Haugesund (June 10, 1940) and “Oldell” in Oslo (July 4, 1940), had been established by Naval Intelligence in London with poorly trained, independent, Norwegians. In the autumn of 1940 however, the British Special Intelligence Service (SIS), prodded by Norway’s Foreign Minister Koht and War Minister Eden, began training Norwegians as radio operators.[5] They decided to establish the next two radio stations in Oslo, (Skylark A) and Trondheim. (Skylark B). On September 5th 1940, four freshly qualified Norwegian radio operators, Sverre Midtskau, Erik Welle-Strand, Finn Juell and Sverre Haug, left Peterhead on the cutter Nordlys, crossed the North Sea and landed at Florø. The men continued on to Bergen where they parted company: Midtskau and Haug travelled to Oslo, and Welle-Strand headed for Trondheim with Finn Juell. In spite of numerous attempts, the group in Oslo never did make contact with London[6]and as we shall see, Midtskau returned to London later in the year. In Trondheim, Erik Welle-Strand struggled to set up Skylark B.

Established in 1910, Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH) merged with the University of Trondheim in 1995 as the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. (NTNU). The institute was, and is still, familiarly called Gløshaugen after the geographic location.

In September 1939, eight hundred and eighty nine young men and women studied in one of the seven departments: Architecture, Geology, Building, Electricity, Chemistry, Machine and General. Among these students were 160 new admissions and an extraordinary intake of 143 foreign students – most of them from technical institutions in Germany. The staff comprised 184 men and women, including 33 professors.

Norwegian students at that time were subject to compulsory military service in which they served six months in three periods taken during their summer holidays. Most of them ended with the rank of sergeant, but others joined Officer Candidate programmes and qualified as Second Lieutenants.

As early as 1938, NTH students had reacted to the vicious Nazi anti-Jewish pogrom of November 9th – The night of broken glass. At a meeting on November 12, they passed a resolution condemning the action and asking German students: “to use all their influence to oppose this tendency in Germany which all friends of the German people follow with sorrow and shame on behalf of European culture.”

On the fateful day, April 9th, 500 students, faculty and staff gathered at Gløshaugen. They had a panoramic view of the German ships in the harbour. The expected mobilization call had not come, the enemy had already occupied key positions and transport services were highly uncertain. Nevertheless, 400 students left Trondheim; most of them in an attempt to reach their units in the south, others, some of them with officer training, on skis to the fortress at Hegra or others eastward towards Sweden.

Fortified by the ‘seasoned’ military students, the Hegra Fortress was the last Norwegian military outpost to give up the fight on May 3rd.

After the futile, unprepared, stopgap, efforts to stem the German advances, students, staff and faculty gradually returned to Gløshaugen. Their will to resist had not weakened and they found new outlets for their passions. So much so, that the NTH became known as The Bulwark of Resistance.

(Source: Holdningskamp og Motstandsvilje) Tapir Forlag

Radio Contact – Skylark B

Skylark B was the third active radio station and the first manned by trained wireless operators.

Erik Welle-Strand (‘Welle’) studied at the prestigious Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH) in Trondheim, so it was natural for him to contact some of his friends and fellow students: Egil Reksten, Lorentz Conradi, Nico Selmer, Haakon Sørbye and Bjørn Rørholt. The latter two were enthusiastic amateur radio operators and technicians. Professor Leif Tronstad was a sympathetic professor for several of these students and at the same time he was actively engaged in the Resitance movement.

The transmitter Welle-Strand had brought from England, a bulky object nicknamed ‘the butter cask’, ran on 220 volts but the voltage in Trondheim was only 150 volts. This meant that the group had to find suitable locations for their station outside the city limits.

Their schedule called for transmissions three times weekly from three different locations. They had to carry the transmitter and heavy batteries to and from the city – a dangerous operation, especially in daylight. Following the instructions ‘Welle’ had brought with him from London, they began tapping out Morse messages. From September 21 until the beginning of November –they tapped away, with n’er an answering ‘dit-da-dit’ (‘R’ for received in Morse). Even when Sørbye had rigged up a new antenne with a much stronger signal, they were unable to make contact. Just before Christmas, they gave up. For one thing, they were running out of locations –which had to be close to a road or path and with access to power lines – for another, the danger of their being caught increased daily. On one occasion, they saw local farmers watching them and had to make up a ‘cock and bull’ story about their activities.[7] On November 26, Midtskau travelled from Oslo to Trondheim to discuss the situation with the men of ‘Skylark B’. They decided that Midtskaug, should return from Oslo, via Stockholm to London with a copy of the schedule to compare it with the one used by SIS. He returned to Oslo next day but getting to London wasn’t as easy as it sounds; it took him almost two months to get there.

About this time, one of ‘Skylark B’s’ reserve WT operators, pilot Per Bugge, announced that he would be leaving for England to join the Royal Air Force (RAF). Reksten decided to gave him a copy of the schedule document as a back-up. The schedules showed Skylark’s transmission days, times and frequencies, these had to be compared with the ones used by SIS. If ‘Skylark’s’ schedules were correct, the group would be informed through a message sent to Trondheim on the BBC’s evening news.

| Arrested | Fate | Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjanes | Ola Jacob | 27.09.1941 | Killed N | Assistant |

| Danielsen | Ina | Courier | ||

| Erlandsen | Yngvar | Killed N | Assistant | |

| Hjelde | Bård Gunnar | 15.08.1941 | Killed N | WT operator |

| Jacobsen | Anton Martin | 15.08.1941 | ||

| Johansen | Einar | Survived war | WT operator | |

| Juell | Finn | Assistant | ||

| Lynner | Bjørn | 07.12.1940 | Killed N | contact Bergen |

| Løken | Alf | 27.09.1941 | Killed N | Assistant |

| Reksten | Egil | ??.09.41 | Survived war | Organisor |

| Rørholt | Bjørn | Survived war | WT/Technician | |

| Selmar | Nicolai | Assistant | ||

| Skeie | Olav | Survived war | WT operator | |

| Sørbye | Haakon | 10.09.1941 | Survived N and war | WT/ technician |

| Welle-Strand | Erik | Survived war | Organisor/WT |

Normally the BBC evening news to Norway began with; “This is the news from London.” However, if Reksten’s schedules turned out to be correct, the preamble would be changed to: “Here comes the news from London.” With Bugge and Midtskauug’s departures, the Skylark team could only worry, wait, enjoy a less than festive Christmas season – and listen to the BBC!

In London too, the lack of signals from Oslo and Trondheim worried ‘Sentralen’ but in the aftermath of the ferocious ‘blitz’, there were many other pressing problems. However, in late January two important messages arrived: Midstskau, from Oslo, had landed in Scotland and Bugge, from Trondheim was at the ‘Patriotic School’[8]. Reksten’s schedule document showed that transmission days were Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The schedule used by ‘Sentralen’[9] showed Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday – Reksten’s was correct – little wonder there had been no connection. But now the problem was solved and SIS-boss Commander Newhill had to accept the blame.

Arnfinn Moland and Ivar Kraglund’s first lines in their introduction to Jan-Anton Poulsson’s book ‘The Heavy Water Raid’ are:

“The Raid on the Heavy Water Plant is imprinted forever on the annals of Norwegian and international war history.”

Anyone seriously interested in understanding why this is so, should read Poulsson’s book – either in the original Norwegian or in the English translation by Ingrid Christophersen. The story has been told many times in other books and on film but, as Poulsson himself writes“some good, some not so good. …They have all irritated me, not only because the actual events have been erroneously portrayed but owing more to the fact that they have been over-dramatized and opinions and words have been

assigned to us which we never either held or expressed.”

Interest in the raid has not dimmed with time – a recent article about the raid, in the New York Times (Nov. 2015) elicited 243 comments.

Scientists at Vemork first observed the curious heavy water in 1934 when it appeared as a by-product of their revised ammonia production process. Physically and chemically, the substance is similar to ordinary water, but while the hydrogen atoms in normal H2O consist of one proton and one electron, many of the hydrogen atoms in heavy water have the added weight of a neutron– an isotope known as deuterium.

On the evening of January 15 1941, the BBC broadcast to Norway began: “Here comes the news from Norway.” In various parts of Norway, the men of Skylark B heard the subtle change in the introduction and understood its meaning. Within a few days they were all back in Trondheim. On Saturday, January 25, London and Trondheim reported signals loud and clear. At last, the men of Trondheim were part of the war – well, almost.

Loud and clear

Disappointment returned next day, and the day after, when the radio waves were silent again. The men of Skylark B blamed the transmitter so Haakon Sørbye built a new one overnight. They also constructed a new receiver, rigged up a new antenna, and found a hiding place under a large spruce tree in an isolated spot in the woods overlooking the city. The new setup resulted in reduced signals towards Trondheim and almost double signal strength towards England. Another NTH student, Einar Johansen, became a welcome addition to the ‘Skylark’ team.[10]

Once contact was established, there was no lack of important information for ‘Skylark B’ to send to London. In addition to the regular reports on troop and ship movements there were two especially important sources. The Germans had taken over Trondheim’s airport at Værnes the day after the invasion, on April 10. Værnes was a critical brick in the building of German domination of Northern Norway and later for attacking allied convoys to and from Murmansk. On April 24th expansion work on the airport began and by the 28th, the first new runway opened, built with the help of hundreds of Norwegian workers. By the end of the war, more than 2000 Norewegians had been employed at Værnes and the airport comprised three runways, several hangers, bunkers and anti-aircraft posisitions – one hundred buildings in all.

On May 16, ‘Welle’ had to leave Trondheim and Egil Reksten took his place as leader. On May 22, Reksten reported that three destroyers had anchored in the harbour and that they had obviously returned from a deep-sea operation. It seemed like an innocuous incident but a few days later Skylark B received a message from London: “Congratulations on the prompt advice about the three destroyers.” These vessels had been escorting the “Bismarck” and Skylark’s message had helped the Admiralty plot the route of the mighty battleship.[11]

Meanwhile, in Trondheim, Knut Haukelid, who had originally worked with ‘Skylark A’ in Oslo, assisted ‘Skylark B’ as a WT operator. He had also managed to get a job working on what the Germans claimed to be an impregnable” submarine bunker in Trondheim harbour. From this position he was able to collect data and other vital information about the construction[12] which Skylark B transmitted to London.

One rather unusual request for information arrived from Eric Welsh, the head of the SIS Norwegian Section.

“Message No 65 For heavens sake keep this under your hat stop try to find out what the germans are doing with the heavy water they produce at rjukan stop…”

Reksten and Rørholt didn’t know much about ‘heavy water’ so they checked with the management at Hydro (the manufacturer). The head of Hydro suspected that a British competitor, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was behind the request, so Reksten and Rørholt composed a cheeky reply:

“Message no 87 stop your no 65 stop we can get the information if you confirm it is important to the present war effort stop If it is only for the ICI please remember that blood is thicker even than heavy water stop”[13]

Professor R.V. Jones the brilliant scientist at the Intelligence Section of the British Air Ministry who had instigated the original request, received the reply and “loved” the thicker even than heavy water part.[14]

The number of messages, not only from Trondheim but from other parts of Norway, grew to such an extent that Einar Johansen complained; “One would think that this is the only active radio station in Norway.”[15] He was right, from May to August 1942 the only active station in Norway was ‘Skylark B.’

SOE

On November 20, 1941 after much uncertainty, many misunderstandings and long discussions, the Norwegian government in London recognised Milorg in Norway as a military organisation – directly subordinate to the Norwegian High Command in London. Co-operation with the British military authorities improved and Norwegians began to volunteer for service in the Special Operations Executive. (SOE). Hugh Dalton had founded SOE on July 19 1940. Its mandate was to organise resistance in occupied countries and to carry out sabotage, “…set Europe ablaze!” enjoined Prime Minister Churchill. At its formation, SOE had taken over ‘Section D’ of the SIS. SIS, however, retained its monopoly on radio communications; a fact that was to cause some operational problems. The ‘Golden Rule’ – that there should be no contact between SIS and SOE operatives – was difficult to follow when SOE agents had to send messages through SIS radio stations.

Churchill strongly supported SOE and he was an ardent advocate, with his Jupiter plan, for invading Norway. Hitler was even more obsessed with Norway in general and Northern Norway in particular. His decision to send his mighty battle-ship Tirpitz to Trondheim was based on his belief that the allies would use Norway as a ‘back-door’ to Europe. Indeed, this was Churchill’s plan. His Jupiter foresaw that; “if things go well…we could advance gradually southward, unrolling the Nazi map of Europe from the top.”[16] Hitler responded by moving troops, naval units, and defence specialists to Norway. He reasoned: “Norway is the zone of destiny in this war” [17]– it was, but not as he had expected.

In London, British and Norwegian authorities had agreed to establish a military organisation in Trøndelag under the leadership of Major Bøckmann and Lieutenant Aune.Both had been active in the Norwegian campaigns after April 9th and were part of the resistance movement afterwards. The objectives were, as before, to provide information about German troop and ship movements. A secondary task was to arm and train Norwegian patriots.[18]

The first arrest

These developments and the previously mentioned activities resulted in a large increase in the volume of radio traffic and with it, the increased possibility of being located. By June 1941, the Germans knew that there was a radio station operating somewhere in the area and had begun their efforts to pinpoint its location. Though aware of the danger, Reksten and his team continued to operate the station but were unable to forestall the inevitable. The end came through lack of experience on the part of the Skylark B team, the German effectiveness at not revealing the arrest of Bård Hjelde, and their eventual success in pinpointing the station.

On August 15th, Bård Hjelde was returning from transmitting at the hidden radio station in Bymarka. He had a fishing rod and other equipment to support his ‘story’ of having been on a fishing trip. A German patrol car stopped and questioned him. The soldiers did not believe his story and they arrested him. At the Gestapo Headquarters, the Mission Hotel, he was tortured and kept in isolation so that his arrest remained a secret.[19]

Hjelde’s disappearance worried the rest of the team but they feared that if the transmissions ceased, the Germans would have a stronger case against him. To avoid this, Haakon Sørbye and Einar Johansen decided to operate the station as usual for the time being. One day when Haakon was alone at the station, he heard an aircraft flying low overhead, it was probably looking for the station. Some days later, Haakon and Einar noticed signs of life in the woods not from their hideaway. They continued to the station however and made contact with Sentralen. Suddenly they heard noises in the bushes; they gathered up a few things, left the transmitter and escaped down an almost perpendicular rockface. They were lucky; the Germans had placed guards at most of the paths leading into and out of the Bymarka woods but the corden had been relieved before Haakon and Einar arrived.

When the ‘Skylark’ men learned that Bård Hjelde had been seen through a window at Vollen Prison, they decided to keep ‘radio silence’ for a while. They moved the transmitter a couple of times, once to a cabin owned by a Professor at NTH after advice from Professor Tronstad and then out into the woods by Jonsvatn. (Lake Jons). However, the Skylark group knew that the end was near and at a “war council,” they decided to send Reken and Bjørn Rørholt to Oslo. Reken was to contact Knut Haukelid while Bjørn was to send messages with Trondheim call signs and schedules on a new transmitter that Haakon Sørbye had built. This was an attempt to mislead the Germans into thinking that the station was still operating in Trondheim.[20]

Another Arrest

On Sept 10, Haakon went to the laboratory at school to do some experiments. A Gestapo thug appeared and stood watching the students as they entered the lab-assistant’s office. He arrested one of them, Rolf Moe. Rolf lived in the same apartment block as Bjørn and Haakon but was not one of their group. Haakon realized that the net was closing so he left the lab and went to see professor Tronstad. He pointed out the Gestapo car outside the building, told the professor about Moe’s arrest and explained the connections between Rolf, Bjørn Rørholt and himself. He added that an accumulator was being charged in Bjørn’s flat. «You must get rid of it, say that you are there to fetch a book if there is any problem», was Tronstad’s advice.[21]

Haakon’s first step was to contact other members of the group to let them know what had happened. He also sent a message to Rørholt in Oslo via the courier, NTH student and Admiral’s daughter, Ina Danielsen.

Haakon reasoned that the Gestapo could not have got a lead on Rørholt so quickly after Moe’s arrest but he was wrong; two Gestapo agents were waiting when he entered the flat. They refused to believe his ‘book’story, he was arrested on the spot and driven to the Gestapo HQ and: “subjected to the familiar German interrogation methods. It was the biggest mistake of my life, but again, an example of how naïve we were.”[22] What Haakon did not know was that Moe’s arrest had led directly to Rørholt because Rørholt had borrowed a backpack from Moe when they last relocated the station. A Norwegian nazi working for the Gestapo had found the abandoned hiding place as he searched the woods. All traces of the operators had been carefully removed, except one; on the ground lay a small clothes tag marked with Rolf Moe’ name. Moe confessed that the name-tag must have come from a back-pack he had loaned to one of the other men in the apartment block.[23]

The net widens, Oslo, Trondheim.

In Oslo, Bjørn Rørholt found that the bomb-damaged German Pocket Battleship “Admiral Scheer” had been in the harbor since September 4. He sent this information to London using his old amateur radio operator’s antenna at his home in Holmenkollen.That evening, the Gestapo surrounded the house and sent men to the front door to arrest him. Bjørn grabbed his father’s pistol and ammunition, ran into the garden, jumped over the fence and exchanged shots with his persuers before disappearing into the woods. Escaping was not easy; the day before, Viggo Hansteen and Rolf Wickstrøm had been executed Martial Law proclaimed with a curfew of 9 pm. Whilst the Gestapo fine-combed the surrounding woods with dogs, Bjørn, helped by neighbours and a doctor, was driven to safety smothered in bandages.[24] Reken was not so lucky. He and Knut had found refuge in a remote cabin on the Hardanger plateau but the Gestapo were on their trail. Haukelid managed to escape, but Reken was arrested and taken to Oslo for interrogation. Back in Trondheim, the Gestapo rounded up most of the Skylark B group and continued looking for the rest. Einar Johansen and Nico Selmar evaded them and escaped to England via Sweden. Alf Løken was arrested during a razzia at the NTH.[25]

Looking for information on Trondheim, I thought I had hit the jackpot when I found a link to Lt. Waldemar Aune on Google. I was wrong. The link was to a group of friends who had a joint football pool and who lived in Waldemar Aune’s Road in Helset, Trondheim

After the Gestapo found code books and ciphers at one of Skylark’s abandoned stations the very foundations of resistance in Trondheim crumbled. On September 22 1941, the Gestapo arrived at Lt. Aune’s home. As we know, Lt. Waldemar Aune had been teamed with Major Brochman to recruit, organize and train men for Resistance work. Amongst Aune’s other activities had been the “export” of Norwegians to England. The Germans had intercepted one of his “transports”, the fishing boat Vita, in the approaches to Namsos some days earlier. While the Gestapo interrogated Aune, another resistance worker, Arthur Mørch Hansson, who had been hiding in Aune’s loft, managed to slip out. He rang the doorbell at neighbour Reidar Jørgensen’s house. Jørgensen was not at home but his wife, Annasof opened the door. Hansson confirmed his identity and told about the unwelcome ‘visitors’ next door. He also said that it was imperative that Professor Leif Tronstad, be warned of the situation. Mrs Jørgensen offered to do the job. Tronstad lived close by and as there was a strong possibility that the Gestapo would be watching his house, Mrs Jørgensen concocted a plausible story for her call. The coast was clear however, so she gave Tronstad the bad news and asked if there were others she should warn. Tronstad asked her to continue to the home of funds manager Magnar Breida.[26] The Gestapo’s interrogation of Lt. Aune could have had serious consequences for these men so Mrs Jørgensen’s warnings were timely. Breida went ‘underground’ immediately. Tronstad and his family were on the train to Oslo at 1915 that same evening, on the first stage of his journey to England, the planning of the Vemork operations, and lasting fame. The Gestapo arrested Aune after his interrogation and he spent the rest of the war in captivity. Bøckman continued his task alone.

Help from Scotland

To assist Bøckman in Trøndelag, two Norwegians, Odd Sørli and Arthur Pevik, left Scotland on February 2 1942 and arrived in Norway 4 days later. Both were SOE agents, trained in sabotage and weapon instruction at the Norwegian Independent Company No.1 (Norisen), later known as the Linge Company.[27] By pure chance, Bjørn Rørholt, (alias Rolf Christiansen), was also onboard. His objective was to report on the Tirpitz. According to Rørholt they left on February 8 – but that’s another story to be told in the next section, Naval Matters.

At their first meeting with Major Bøckman, the two SOE men explained the directives they had received for the new organization in Trøndelag. The main points were: the training of young Norwegians in modern guerrilla warfare, reception and storing of arms, ammunition and supplies, direct radio communication with London, and the least possible connection with other illegal groups of any kind. Because of the many recent arrests and informer activities in Trøndelag, Major Bøckman was not entirely happy with the two first tasks but he had to accept the joint decision from London. Lark 1 was the codename for the operation and Odd Sørli was the man in charge.

The background for Lark (and the Skylark B operation), was Churchill’s special interest in Norway. In January 1942, he had written to his Chief of Staff, General Ismay: “The presence of Tirpitz at Trondheim has now been known for three days. The destruction or even the crippling of this ship is the greatest event at sea at the present time.”[28] On May 1, he wrote to Ismay again about ‘Operation Jupiter,’ his plan for a second front in Norway. He was still hoping for ‘Jupiter’ at the beginning of July but neither his own military advisors nor his new allies in America supported him.

In Norway, however, the Anglo/Norwegian attacks on Lofoten and Måløy had been perceived by the Norwegians as preludes to a full invasion of Norway. Odd Sørli and Arthur Pevik set about activating the somewhat depressed resistance in Trondheim. Both had brothers, Oivind Sørli and Johnny Pevik, who were similarly enthusiastic patriots. SOE man Herluf Nygaard, who had already made contacts for Bøckman in Åndalsnes, Ålesund, Molde, Kristiansund, Namsos and Hegra, completed an effective troika. These three had the advantage that they could wander around Trondheim freely at all times whereas Odd Sørli and Arthur Pevik were known locally to have been in England and they could only venture outside after dark.

Radios and Weapons

Lark’s biggest problem at this time was the lack of radio contact with England; in fact, they had no radio. Nygaard, always eager for action, volunteered to make the trip to England via Stockholm. Odd Sørli agreed and on March 7 1942, Nygaard and Arthur Pevik left for Stockholm. It was a short visit – they left Stockholm by ‘plane to London three weeks later. Malcolm Munthe met them in London. Munthe had experienced the opening phases of the German occupation in Norway, he had worked for the British in Stockholm and was currently the liaison officer between SOE and the Linge Company men. Nygaard met with other SOE leaders and trained at the Linge Company facility in Scotland. After a hazardous North Sea crossing on the cutter ‘Jack’, Nygaard was back in Trondheim on April 24. He had with him a radio transmitter and a fellow Linge-man and radio operator, Evald Hansen. Shortly afterwards two other Linge-men, Olav Sættem and Arne Christiansen landed at Dyrøy from the Shetlands with a supply of explosives and weapons that had to be hidden locally.

Sættem and Christiansen made their way to Trondheim. They were the new weapons instructors for Lark and they each took one set of instructions and weapons with them. Odd Sørli had a third set. This was hardly enough to prepare for an invasion so they had to fetch more from the weapon depot at Dyrøy. Fish was the most common commodity in that part of Norway and fish was usually transported in crates. In an elaborate scheme, involving many contacts, the Lark men packed weapons in specially made crates, covered with peat, heather, thick paper and finally a layer of fish. The German inspectors at the harbour could see the fish through the slats at the top. All went well and the two instructors began a period of training recruits from all parts of Trøndelag. These newlytrained men returned to their districts to organise and train new groups – especially near military installations, railways, and highways.[29]

Sættem and Christiansen were recalled to Stockolm on July 20. Radio-operator Evald Hansen, who had had a hectic three months in a nerve-racking and vulnerable position, went with them. He had arranged for another radio-operator, Olaf Gjølme, to take his place. Gjølme could only operate the station ‘part time’ so communications suffered. Early in September, Odd Sørli was also recalled to Stockholm and Herluf Nygaard took over as Lark’s leader. He kept Major Bøckmann up to date on his activities but Bøckmann could only reach Nygaard via a third party. Close associates Knut Brodtkorp Dannielsen, Øivind Sørli, Herbert Helgesen, and Rolf Trøite separated Nygaard from the various local groups in the growing organisation. Helgesen was especially important because of his many contacts in Trondheim – including police and Nazi circles.[30]

Because of the poor radio connections with London at this time, most of the instructions and information travelled by rail to Oslo and then relayed to Stockholm. The German never discovered the identity of the contact at the railway station in Trondheim. His opposite number at the East station in Oslo was the stationmaster himself.[31] The Lark group concentrated on local matters: organising medical services, training couriers, and securing supplies – including the all-important ration cards for food and fuel. Lark was still hoping for more arms and ammunition from England and had begun to plan for possible airdrops.

Sabotage, Reprisals, Persecution

Addresseavisen Trondheim

Announcement from the Supreme SS and Police Commander, North.

In connection with the conditions of the State of Emergency…

the following Norwegian citzens were executed at 6 pm on October 6, 1942….

The entire fortunes of the executed have been confiscated.

Signed Rediess SS-Oberruppenfuhrer und General der Deutschen Polizei.

Other events effected Lark’s situation in Trøndelag. The Linge Company’s attack on the transformer station at Bårdshaug in May had resulted in closer control of ships-traffic by the Gestapo and the end of supplies by sea from England. In Vefsnadalen, Capt. Sjøberg had been operating undisturbed since autumn 1941 but in September 1942, the Gestapo became suspicious. Following a shooting incident at Majavatn a large contingent of German troops and police fine-combed the district. The Linge leaders escaped, but the Gestapo imprisoned many local inhabitants. On September 6th another Linge group had led a successful attack on a power station at Glomfjord. This was too much for the Germans. On October 6th the German Chief of Police in Northern Norway, Wilhelm Rediess, declared a state of emergency in Trondheim, parts of South-Trøndelag, the entire North-Trøndelag and part of Nordland. In the same declaration, he announced that in reprisal, 10 leading Trondheim citizens would be executed. Another 23 of those captured after the Majavatn episode were also sentenced to death. These events had a further depressing effect on the resistance organisations in Trøndelag.[32]

Another disturbing development was the intense persecution of the Jewish population that began in Trondheim before spreading to the rest of the country. The confiscation of the Trondheim synagogue in April 1941 was the first sign of Nazi intentions. In the autumn of that year, Ernst Flesch, a ruthless anti-Semite, had become commander of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD – Security Service) for Trondheim, Trøndelag, and Møre and Romsdal. By the summer of 1942 he had ‘taken over’ almost all the businesses owned by Jews in these areas – and arrested the owners. He arrested four other Jews and executed them for listening to and spreading Norwegian news from London.[33] The mass-arrests of Trondheim Jews in October 1942 were the first in the country – but not the last.

Rinnan Gang

The traitor Henry Oliver Rinnan is said to have been responsible for 80% of all arrests in Trøndelag during the war. It has also been claimed that more books and articles have been written about Rinnan than about any other Norwegian involved in the war.

Rinnan was born on May 14 1915 in Levanger. He started his nefarious career in the summer of 1941 when the Gestapo ‘employed’ him as an agent – or informer – in central Norway. His nickname was ‘Lola’, and his group became known by this name. He transferred his ‘services’ to the German Security Police in March 1942. Commander Flesch ordered Rinnan to find suitable recruits as ‘V-men’ – i.e. trusted men who would knowingly work for the Security Police by gathering information and infiltrating resistance groups. By the end of 1942, Rinnan had selected 20-30 men and women (‘positive contacts’) who became the nucleus of his ‘Lola gang’. Rinnan and his gang worked closely with Flesch and the leader of Section IV, Gemmecke, both of whom were extremely capable and efficient officers.

However, the ‘success’ of Rinnan’s operation was mostly due to a system that he claimed to have developed himself: gang members, posing as patriots, approached resistance groups and individual members either with offers of help or with requests to become involved. To build up credibility Rinnan’s men could provide arms, cigarettes, ‘illegal’ newspapers and other ‘imported’ goods. Rinnan went to great lengths to convince his ‘negative contacts’ that they were actually working for the resistance. On one occasion he arranged to ‘assist’ an ‘arrested’ resistance worker, to escape to Sweden. Two of his most devastating actions were in the Majavatn and the Vikna episodes. According to Rinnan’s testimony at his trial, his ‘negative contacts’ numbered 150 – 250 ‘good Norwegians.’[34]

Tirpitz[35]

Radio-operator Evald Hansen returned from Stockholm at the beginning of October 1942 with a new pseudonym – Egil Halvorsen – and in high spirits after his two months in Stockholm. Throughout the summer the British had been trying, unsuccessfully, to put the Tirpitz out of action by air. In September it looked as though a new, more ambitious plan – attack by mini-submarines, or X-craft – would succeed. The Lark team, again in daily contact with London, felt encouraged to be part of such an important operation. They were in good spirits too because they knew that Rinnan had tried, but failed, to infiltrate the organisation – Lark remained intact.[36]

Unfortunately, the mini-submarine attack, Operation Title, failed, leaving a sense of anti-climax among Lark operatives. With no major actions and no supplies by either sea or air, they concentrated on the organisation. New groups were established in Oppdal, Heimdal, Tydalen, Klæbu, Skogn and Værdalen. A new leader Leif Wiger, strengthened the group at the Norwegian Institute of Technology. This expansion may have accounted for the rumour that a radio – detection unit had been seen in Trondheim. Rumour or not, Nygaard decided to move the radio station to a safer location in Jørundsgate, and to find different lodgings for himself.

Internationally, the war situation was changing: German advances in Russia and North Africa stalled, the Americans landed in Morocco and Algeria, bombing raids on German cities increased and so did optimism in the Allied camp. But had Norway been forgotten?[37]

Arrests, torture, death.

It seemed that way until December 15, 1942 when Evald Hansen brought some good news from his daily report: London anticipated a weapon drop on December 17th. The final decision would be made on the 16th – could Lark be ready? The answer confirming this was to be sent at 1300. Nygaard ordered two men to be ready to be at the drop-zone on the and arranged to meet Hansen at the bus-station at 1330. Hansen didn’t show up on time and after waiting almost an hour Nygaard decided he had to find out what was happening. Jørundsgate was quiet, few people, no cars, and not a German in sight. As he opened the door however, he was dragged inside by a civilian-clad German who asked where he was going. Nygaard knew that the radio was on the second floor and that an NTH student lived on the same floor so he said he was visiting the student to get some books. The student wasn’t home, so Nygaard’s guard pushed him towards Hansen’s room. As the German moved to open the door, Nygaard punched him– but not hard enough to knock him down. Nygaard started down the stairs. His long winter coat trailed behind, his pursuer trod on the coat, pulled Nygaard backwards, and jumped over him. Other Germans joined the fray, hoisted Nygaard up, and into the radio-room where Hansen sat at the transmitter surrounded by uniformed Gestapo agents.

Nygaard and Hansen claimed that they didn’t know each other but the Germans didn’t believe them. They bundled Nygaard down the stairs again and headed towards a waiting car. At that moment, Olav Reiersen, one of Nygaard’s men, who was on his way to visit Hansen, quickly but unobtrusively, changed his course and continued his stroll along the street. This chance meeting was a great comfort to Nygaard because he knew that Reiersen would warn the other Lark operatives of his arrest – and, if necessary, they would go into hiding. [38]

The Germans forced Hansen to continue transmitting messages to London in the hope that they would get more information about the resistance in Trondheim. But in each transmission, he included a hidden code that told the receiver that the sender was working under enemy pressure.

The Gestapo, however, had another form of pressure – torture. Herluf Nygaard was the first to be interrogated – a kind word for brutal methods of breaking a man’s spirit. Nygaard managed to hold out, then pretended to co-operate and finally, en-route to another prison, escaped after a chase through the streets of Trondheim. He reached Sweden, then England and returned to Norway to continue resistance during the war and a distinguished military career afterwards. Sergeant Evald Hansen suffered the same kind of torture as Nygaard, again without disclosing anything of interest to his tormenters. In addition, he spent two months in solitary confinement at Gestapo headquarters and endured both water and heat torture. He died from the mistreatment on April 5 1943 at Innherred hospital. The St. Olav’s Medal with Oak-leaf was awarded posthumously to Hansen.[39] The arrest of Nygaard and Hansen signalled the effective end of another phase of Lark. Once again the Allies were without eyes and ears in Trondheim.

The ruthlessness and efficiency of SD boss Ernst Flesch and his second in command, Walter Gemmecke spread fear and loathing throughout north-central Norway. Local resistance groups, SIS radio stations, and imported Linge Co. groups such as Lark were constantly under pressure and scrutiny. The separate, and often more aggressive, Communist resistance groups Thingstad and Wærdahl, were almost obliterated by round-ups, imprisonment, and executions. There was little contact between the local resistance organizations in Trondheim and Oslo so the possibilities for developing an effective Milorg organization were limited. In addition, the Rinnan gang grew in size and effectiveness. 1942 was a bad year.

New year – New faces

Johnny Pevik, Nils Uhlin Hansen, Odd Sørli and Erik Gjems-Onstad (EGO) came to Trondeim in February 1943. The four Linge-men had trained together in Scotland and Sørli, who had been in Trondheim before, emphasised that they were joining an established organisation and that a new stage had begun for Lark Blue. By sending four men to Trondheim, it seemed obvious that SOE had high-hopes for positive results from the station. however, from the first meeting with Jens Beer, one of the key men in Trondheim’s Milorg, EGO recalled one sentence: “We will give you all the assistance you require but at sabotage, we pass.” This sounded depressingly negative but as he got to know Jens and his men better, EGO realised that their attitude reflected neither weakness nor apathy. The Martial Law in 1942, the arrests, the tortures and the executions had shocked everybody and were still intimidating factors.

By the beginning of summer 1943 the Milorg organisation in Trøndelag comprised 8-900 men: about 130 at NTH, 300 in Trondheim, and 20-30 in each of the other 3 areas. Many of these had received weapon training in 1942 after a supply of arms had been shipped from England in January[40], but there had been no centrally-led training in 1942. A great deal of information about German army and naval installations had been forwarded to the Allies and large dumps of arms and ammunition had been established throughout the region. Expectations of an Allied invasion were great – but so was the uncertainty – thanks to the activities of the ever-growing Rinnan-gang.

The civilian resistance in Trondehim remained active but separate from the above. In 1943 Reidar Jørgensen was ordered to Oslo where he met a Milorg representative from the ‘Central Leadership. (SL) This man told Jørgensen that SL had decided that the Resistance in Trondheim should establish a “withdrawn” Milorg leadership. This group should have no direct contact with any of the other groups in Trondheim, but make sure that it was intact when the end of the war came in sight – and only react on secure orders from Oslo. The three men chosen as the leader-team were, Professor Inge Lyse as Foreman, with fishmonger Krøtøy and Jørgensen himself as assistants. According to Jørgensen, nothing sensational happened during this period but in the autumn of 1944, Lyse and Krøtøy had to flee to Sweden. It was not until early 1945 that they were replaced by Professor Erling Gjone and Johan Karlsen. In the interim Jørgensen; “sat alone, without connections or contact with SL – probably because I was assumed to be under suspicion”[41]

Lark Blue

To begin with, EGO, the radio operator for Lark Blue, had difficulties in making contact with Home Station.[42] He had only managed to rig up an internal antenna and after many fruitless hours trying he realised that this was the problem. With the help of NTH student Svend B Svendsen he found another location where he could string out an antenna over a roof – and, finally, made contact. By summer, Lark Blue consisted of three radios, in three different locations that were in connect with London 4 times weekly. The volume of traffic was rather more than security allowed, but London refused to cut back; not even when a double-agent reported that the Gestapo claimed to have a bearing on a radio transmitter in Trondheim. However, to minimise the risk to EGO, London agreed to send “blind” – that is, Lark should not answer their call signal but only listen and receive messages. Lark’s own transmissions were restricted to short, urgent, messages.

This self-imposed radio silence meant the disruption of the radio connection with the British Legation in Stockholm. The Meråker railway line provided a suitable alternative and the train personell became reliable couriers for Lark. On almost every journey messages were transported to and from Stockholm.

In London, the spectre of Tirpitz still haunted Allied thoughts and created tasks for Milorg, but the warship had left Trondheim and never came back. Sørli’s other activities with Milorg included the movement and hiding of weapon stores and the continuous recruitment of men and women for the organisation.

Assassination Attempts

Strengthening the organisation was one thing; protecting it against the Gestapo and informers was another. The Allied offensives in Europe and Africa meant that there would be no major attack on Norway for the foreseeable future so the emphasis must be to maintain Milorg’s strength for the final phase of the war. Odd Sørli went to Stockholm to discuss the situation and reached an agreement to defend the organisation by attacking the informers. The plan was to lure Henry Rinnan to a meeting close to the Swedish border, kidnap him, press him for information, and then liquidate him. Easier said than done but with anonymous letters and newspaper notices the attempt was made. Rinnan wouldn’t rise to the bait so they reverted to Plan B; Johnny Pevik, Brodtkorb-Danielsen, Frederick Brekke, and Ole Halvorsen left Stockholm with orders to liquidate Rinnan (Operation Wagtail). In the meantime, Rinnan responded to the first plan and four more men were sent from Stockholm in an attempt to make sure that one of the plans worked. Both groups, travelling separately overland, ran into serious snow storms but eventually arrived in Trondheim towards the end of September.

Both groups had had strict orders to avoid contact with other resistance groups in Trondheim, including Lark. On October 6 1943, Pevik, Danielsen and Halvorsen waited outside Rinnan’s home. Details of the events that followed are uncertain because of conflicting reports. What is certain is that one of Rinnan’s aides, Bjørn Dolmen was shot and wounded, that shots were fired at Pevik’s men wounding Halvorsen, and that Rinnan escaped unharmed. There has been speculation that Rinnan had been warned of the assassination attempt, possibly by Brekke, but this has not been proved. Pevik took the unjured man to a nearby ‘safe house’ not knowing that Lark’s transmitter was located there. A friendly doctor took care of Halvorsen’s wounds and after a few days they were able to get him on the train to Oslo and out of danger. Dolmen recovered after two weeks, Rinnan was unharmed and the assassination attempt had failed. Odd Sørli returned from Stockholm shortly afterwards. He was not happy with the news of the contact between Pevik and Lark – and even less happy when he heard that the radio station/safe house had been used as a hospital.

In the middle of October, Johnny Pevik and Danielsen headed for Namdal with false identity papers. Their orders were to lay low, obtain some kind of work and prepare for future drops of supplies and ammunition. At Harran they got work as woodcutters at the Hemanstad farm but the local Milorg men were not sure about the newcomers. Were they to be trusted? Or were they Rinnan’s men? Mistrust and uncertainty pervaded the atmosphere in Trøndelag at that time because of the effectiveness of Rinnan’s informer network. The local Milorg leader checked with his contact in Stockholm who replied that he knew of no British agents in their district. Pevik and Danielsen were thus branded as provocateurs and denounced to the Gestapo. Danielsen was away in the village when the Germans surrounded the cabin. He escaped to Sweden. Pevik was arrested. When the locals saw him paraded through the district in chains they realised that they had been the victims of a terrible misunderstanding.[43] Pevic was taken to Gestapo headquarters in Trondheim. How he managed to survive the horrors of Gestapo torture for over a year is impossible to imagine. On November 19, 1944 he was hanged in the cellars of the Mission Hotel. His torturers, including Rinnen and Grande, were unable to obtain any information from him.[44] King Haakon VII awarded Johnny Pevik the Norwegian War Medal posthumously for his “courage and resolution.”

In Sørli’s opinion, Ivar Grande, Rinnan’s second in command, was just as dangerous as his boss. Sørli and Gjems-Onstad made two separate assassination attempts on Ivar Grande but neither was successful. Rinnan always claimed that he led a “charmed life.” Certainly he survived the war and his network of negative contacts, co-operating with the Gestapo, infiltrated and destroyed several Milorg groups outside Trondheim. It seemed only a question of time before they reached the inner core of the ‘Lark’ organisation.

End of Lark Blue/Lark Green

In this tense situation, security at the radio station was strengthened, the name changed from Lark Blue to Lark Green, and a more sophisticated code system activated. London ordered Gjems-Onstad to find another radio operator so that he, EGO, could go to Kristiansund to assist in creating a military organisation there.

After only a short time in Trondheim, Odd Sørli was called to Stockholm to report on the situation. A few days later, Gjems-Onstad had a narrow escape when visiting friends. He rang the doorbell but instead of a friendly welcome, two uniformed policemen faced him. At the same time, he heard a voice cry out: “We are all arrested.” He spun around and raced down the street – luckily, without being chased or shot.

He reported this latest incident and two days later was ordered to close down the station and make his way to Sweden. He left Trondheim on October 29 1943. With Lark Green disbanded Leif Wiger and Jens Beer took over the Milorg organisation. In December, the Gestapo arrested Leif Wiger, Jens and Martin Beer and several other leaders. Other Milorg men escaped to Sweden and Trondheim was once again isolated. But things had been happening in other parts of Trønderlag.

Thamshavn – Linge Co. and Milorg

Not far from Trondheim, the Thamshavn Railroad, was the first electric railway in Norway. It was built in 1908 to carry ore from the Orkla mines at Meldal in South Trøndelag to the harbour at Orkanger. Pyrite ore was essential to the German munitions industry and disruption of the supply from Norway was a high priority for the Allies. The first attack, Operation Redshank, with SOE/Linge agents Petter Deinboll, Per Getz and Thorleif Grong, had destroyed the transformers at Bårdshaug in May 1942 and the men returned safely to England. The destruction seriously interrupted both mining and transportation for three months. [45]

In September Lt. Deinboll was back in Norway again together with Bjørn Pedersen and Olav Sættem. Their target this time was the loading facility at Thamshavn. Because of the longer than normal trip across the North Sea, and local organising difficulties it was January 1943 before they, and their equipment were ready. The first plan had been to destroy the pier but local experts advised against this. Instead they decided to sink a fully loaded German freighter just before it departed. On February 21 the five thousand ton Nordfahrt tied up and loading began. Soon after midnight on February 26 a small rowing boat slid out towards the freighter. Arc-lights lit up the ship and much of the harbour but the ship itself provided a tiny sliver of shadow. Expecting to be sighted at any minute, the men fixed the charges and silently rowed away. The Nordfahrt sank, the operation was a success and after an eventful, strenuous and near-fatal period in the winter-decked mountains, the three men returned safely to England. [46]

Though successful, the sinking of the Nordfahrt had no significant effect on the ore supply to Germany. Lt. Deinboll, by now a veteran, was given a new task: to destroy the machinery powering the lifts in the more important mine-shafts or, alternatively, attack the railroad again. Arne Hægstad, Pål Skjærpe, Torfinn Bjørnås, Aasmund Wisløf, Leif Brønn and Odd Nilsen, as second-in-command, comprised the Linge group that was dropped by parachute on October 10th. From their refuge in a primitive cabin, reconnaissance showed them that the Germans fully expected new attacks: extra barbed-wire, flood-lighting and anti-personnel mines revealed this clearly. Deinboll decided to go for the alternative – nine of the fourteen locomotives plying between the various stations. The complicated attack took place in the early hours of October 31 – with impressive results: 5 locomotives destroyed, 1 locomotive damaged so much that it had to be sent to Oslo for repairs, freight-cars and a bogey destroyed, and several buildings damaged. Deinboll was not satisfied; one important locomotive remained capable of maintaining the ore transport. He decided to attempt to destroy this and another locomotive at the same time. On November 17 an electric charge exploded as Odd Nilsen was fixing it to a rail – killing him instantly. Deinboll called off the action but Bjørnås, unaware of the accident, destroyed his target as planned. (Operation Feather)

The group had hoped to remain in the district to make a further attack. However, the intense German attempts to find them, and the capture of Pål Skjærpe ruled out this possibility and the four remaining saboteurs made their way back to England.[47]

After the Germans lost their supply of Sicilian ore in the summer of 1943, the importance of the supply from the Orkla mines increased. The October and November attacks reduced the flow – but not sufficiently. SOE assigned Linge men Arne Hægstad, Torfinn Bjørnås and Aasmund Wisløff to destroy the remaining locomotives. Code-named Feather II they arrived in Norway on April 21 1944 via Sweden.

New plans, new assignments

Meanwhile, Odd Sørli had been in London discussing future plans, Ingebrigt Gausland was sent from Stockholm to Trondheim to assess the situation there, and Erik Gjems-Onstad attended a course in Stockholm on ‘Psychological Warfare’ which he described as “Completely new and strange.” In January 1944 Sørli returned from London and was assigned to Stockholm as ‘district specialist for Trøndelag.’ Gjems-Onstad was posted to Trondheim to take over Lark, re-organize Milorg, and establish a new organization for psychological warfare – codenamed Durham. He left Stockholm on March 27 1944 together with Ingebrigt Gausland and Harald Larsen. He was ordered to return in two months if possible.

In Stockholm, Gjems-Onstad had been told that Ivar Faye Rode would be a good man to head and re-build Milorg in Trondheim. Rode was not unwilling, but because of his bad experiences with informers and provocateurs he refused to accept the weapons, hand-grenades, poison-pills, and even the propaganda material as positive proof that Gjems-Onstad’s was not a provocateur. As a last resort, EGO gave Rode a few details of a sabotage action that would occur within 14 days not far from Trondheim. “When this happens,” he said, “you will know that I am who I say I am – and that our first job together will be to get the three saboteurs safely away.” He was referring to the Feather II operation.

Orkla – Feather II

The Milorg group in Orkla, one of the strongest and most reliable in Trøndelag, made the necessary arrangements and provided information for the three men of Feather II. A local farmer built them a concealed hideaway in the woods close to the railroad at a point where they planned to destroy three locomotives and, if possible, a bridge.

On May 9 and June 1 1944, respectively, the trains were hi-jacked, the passengers dispersed and the locomotives destroyed. A third action, on June 10 back-fired – the train was heavily guarded and in the exchange of fire, two Germans were shot.[48]The shooting resulted in an intensive search for the saboteurs and the Germans offered a reward for their capture.

To create a red-herring, Gjems-Onstad called the police and said that he had seen three men who looked like the fugitives – at a location far away from railway. Naturally, he didn’t try to collect the reward. The first attempt to arrange a meeting with the Linge men failed, but they eventually managed to reach Trondheim. They were taken care of, rested, and on June 19 1944 they set off on the first leg of their journey by train, truck, and finally on foot to Sweden. The Thameshavn sabotage convinced Ivar Faye Rode of Gjems-Onstad’s identity and thus began another new phase for Milorg in Trondheim

On June 21, Gjems-Onstad visited North Trøndelag to contact agents, enlist new recruits, and evaluate Milorg’s strength. At Hegra he visited Rolf and Nils Trøite, old friends who had been steadfast Milorg supporters since 1941. On his return trip, he found that Rolf and Nils had been arrested the day after his visit – probably because the brothers had aided the Thameshavn saboteurs during their escape. After this inspection journey, Gjems-Onstad returned to Stockholm and reported on the situation in Trondheim.

Trondheim – new arrests

Gjems-Onstad, with newly-trained couriers Rolf Olsen and Egil Løkse, who was also a radio-operator, returned to Trondheim in August. Reports from ‘Durham’ and Milorg were positive but both complained of lack of material and supplies. The leaders agreed that couriers and parachute-drops must be increased if the organisations were to become effective.

Gjems-Onstad stayed with Herleif Halvorsen and after a few weeks, when a stranger began to ask for a meeting with ‘Leif Knudsen’ – EGO’s alias – they realized that their security was in danger. EGO and Halvorsen’s fiancé Eva Munthe, decided to leave for Stockholm immediately but Halvorsen chose to stay. That night the Gestapo came to his apartment. He heard them breaking in, ran up to the loft and dived into the river. His pursuers heard the splash, searchlights lit up the river, and they sent a boat over to the other side. But to no avail – Halvorsen escaped and found cover in a safe-house despite the fact that he had lost his pyjama trousers during his swim.

Egil Løkse was arrested next day when he went to visit Halvorsen. Løkse had no way of explaining his visit. His identity card was as false as his name – as he was a radio-operator the Germans thought they had captured Leif Knudsen. But EGO was safely in Stockholm where he received an urgent signal from London asking him to confirm that Løkse had been arrested and he devised a control question that London could send to Løkse. Løkse’s reply confirmed that he was sending under scrutiny. Løkse, knew none of the Milorg leaders in Trondheim but the Gestapo thought he did and ‘interrogated’ him brutally.

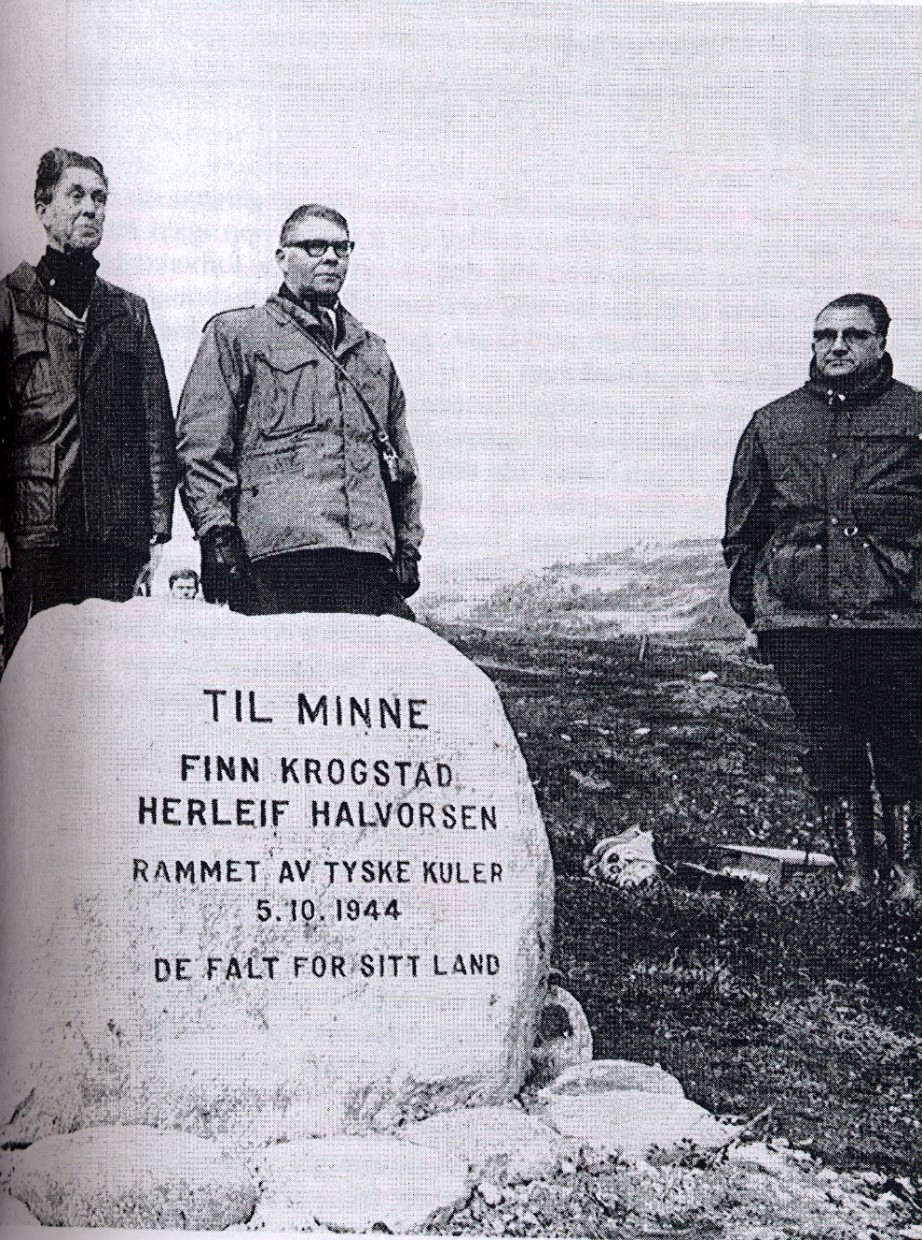

On September 24 the arrest of Ivar Faye Rode and Asbjørn Hørgaard indicated the beginning of another round-up of Milorg leaders. Herleif Halvorsen, Finn Krogstad, and Rolf Leer started off for Sweden with three others. On October 5 1944 they were caught unawares by a German patrol not far from the Swedish border, Halvorsen and Krogstad were shot. Krogstad died immediately, Halvorsen, crawled over the border where he died and was not found until the following year. Once again Milorg in Trondheim had been decimated but ‘Durham’ remained intact. A few weeks later a group of men arrived in Stockholm – the remnants of the once sturdy Milorg group in Levanger. Informers and infiltrators had won the day there also.

On September 24 the arrest of Ivar Faye Rode and Asbjørn Hørgaard indicated the beginning of another round-up of Milorg leaders. Herleif Halvorsen, Finn Krogstad, and Rolf Leer started off for Sweden with three others. On October 5 1944 they were caught unawares by a German patrol not far from the Swedish border, Halvorsen and Krogstad were shot. Krogstad died immediately, Halvorsen, crawled over the border where he died and was not found until the following year. Once again Milorg in Trondheim had been decimated but ‘Durham’ remained intact. A few weeks later a group of men arrived in Stockholm – the remnants of the once sturdy Milorg group in Levanger. Informers and infiltrators had won the day there also.

New Strategy

By October 1944, the focus of the Norwegian resistance had switched from sabotage to being prepared for the end of the war in mainland Europe. What would the more than 350,000 German soldiers, sailors, and airmen in Norway do when this happened? Would their leaders respect the orders of a defeated war-machine in Germany? Or would they continue to fight for the 3rd Reich? On October 30, Gjems-Onstad once again left Stockholm with instructions to check if it would be possible to rebuild the Milorg organisation in Trondheim, re-establish the Lark radio station, and begin to prepare for defences against German destruction in the event of a warlike finale.

Special troops who were to be deployed in any actual conflicts in Trøndelag were already being trained in Scotland – codenamed Crowfield and Polar Bear 2. EGO’s tasks were to find contacts, arrange drop-zones, provide accommodations, establish communications and, not the least important, collect information about German withdrawal plans. For the latter task, the intelligence expert, Ship-broker John Hansen, continued to operate securely in Trondheim. Particularly valuable to the Allies were the detailed information Lark sent concerning troop movements through Trondheim and ship dockings and convoy movements in the harbour.

Trondheim – more new faces

Otherwise in Trondheim, Anne Øverås, a teacher at the Cathedral School, had already made her mark as messenger and post-drop. Steinar Tønsberg, who worked in the police department, provided her with travel documents so she could roam the county gathering both information and contacts. One of her first contacts, Jenny Johansen, owned a bakery – she supplied bread of all kinds to the Milorg men during that last winter. As many men had been arrested or were in exile abroad, women became more and more active in Trondheim.

Their efforts did not go unnoticed: The British Government awarded the King’s Medal for Courage to Anne Øverås and Jenny Johansen after the war. The Norwegian Government fined Jenny Johansen for selling bread to people without ration cards.

On November 22 the following telegram arrived: “Give a short report on your opinion of ‘Lark’s’ situation.” Gjem-Onstad replied:

Have contact with Heimdal and Orkdal. Orkdal now OK with new leader.

No new arrests, some expansion Heimdal.

No joint leadership.

In Trondheim, ‘Durham’ could expand to include weapon-training

New groups like Polar Bear – with specialists from UK highly desirable.

Difficult to find suitable district leaders for Lark

Suggest either ‘withdrawn’ district leaders take over, or that districts merge with home forces and Linge-men take charge.

He asked for a prompt, if temporary, reply.

Anne Øverås and two of her friends[49] approached EGO with the idea of starting a new illegal newspaper. They were willing work on this but felt that they had to have ‘official’ backing and a reliable source of news. At that time there was no regular ‘illegal’ news distribution in Trondheim so EGO felt justified in telling them to go ahead. He told Stockholm of the venture and shortly afterwards the first copies of “For Friheten” (For Freedom), were distributed.

In a report to Stockholm on November 28, EGO described the situation in Trøndelag and Trondheim with specific reference to couriers, ‘Durham’, and Milorg leadership. He also included the information about troop transports and railroads “to show that we have good contacts.” In an appendix to the report he analysed some of the background for his strong support of the illegal newspaper. He claimed that one of weaknesses in Trøndelag was the alienation between the fronts ‘at home’, and ‘abroad.’ Lack of reliable information was the most important reason for this. In the early stages of the war people were involved and interested. They got to know what was happening abroad, but as illegal’ news was stifled, and Gestapo control hardened, the man-in-the-street gradually became isolated. Rumours, rather than real news became the currency of communications and not even the official ‘orders of the day’ carried much weight. He gave several examples to support his views. He closed by anticipating the response “…We could, and should, have done more, but now it is too late,.” by claiming that fresh news and propaganda would have a good effect on morale and contribute to better post-war understanding and co-operation between those at home and those abroad.

There had been no “prompt reply” to EGO’s situation report of November 22 so on December 12 he wrote to Stockholm with an update. Because of suspected infiltration, the Heimdal group had almost ceased to exist and the only operational group now was at Orkdal. In Trondheim he had two new small groups for Lark –one of which would be integrated with Polar Bear. ‘Durham’ continued to operate independently and successfully, so much so, in fact, that things had become almost ‘routine’ and the men needed “new impulses and new ideas.” He complained that he too, had comparatively little to do, and had not taken much initiative in this respect because: “…in the past month I have received 4 reminders to be careful and to keep strictly within the limits of my operational order.” He asked for clarification regarding ‘Lark’, permission to involve himself with Durham and possible new tasks. At the same time, he reported the success of a new radio connection with Stockholm and requested a new radio and a new operator to reduce the risk of detection.

Odd Sørli replied on Jan 2nd that he had sent the report on to London and that he was thinking about sending a good operator even before the OK came back.

No new operator arrived, but the courier route over Sul, well-worn by ‘Durham’s’ requirements, worked so effectively that radio contact became less important.

New orders – new reports

On November 18th Home Office advised that two Linge-men would soon be arriving in Trondheim but it was not until Christmas Eve that Torfinn Bjørnaas arrived. He had two letters for EGO from Stockholm. The first outlined new orders:

We are sending this message by N.3 (Bjørnaas) who will now be joining you as instructor.

Headquarters consider that you should yourself, as far as LARK is concerned, work outside the towns of Trondhjem and Strinda….

N.3 should begin his work in area 7 (Heimdal) as you yourself have suggested…No action of any kind should be taken except under orders from headquarters.

If N.3 is to do rat-work, he will receive special orders regarding this from headquarters.

Arms for instructional purposes for the use of N.3 will be sent in from here by the next available courier. … but obviously if the men trained by N.3 are to be effective, you will require arms on a large scale and we suggest that you try to arrange for a drop with headquarters.

The second letter thanked EGO for his useful suggestions regarding ‘Durham’ and for his thoughts about propaganda in general[50]. This letter from “Uncle” (Consul Tom Nielsen in Stockholm) inspired EGO to write detailed reports on two local events that effected people’s attitude to the occupation in different ways. The first was a summons to attend an NS meeting that was received by many families at the beginning of January. County commissioner Rogstad was to be the speaker and his theme was ‘Settling accounts with the Resistance.’ Rumour had it that he intended to ‘read an obituary’ over the organisation. Most people, remembering the arrests after a previous meeting, were afraid of reprisals if they did not attend. A campaign to keep folk from attending was not too effective but the new illegal newspaper ‘For Freedom’ made an impact. The meeting halls were full but Rogstad’s revelations impressed few and frightened fewer. On the contrary, he spread positive publicity for the Resistance movement and he sparked an interest for its work that previously had been totally absent.

His second report concerned the sabotage of the Jørstad Bridge on January 13th. Many rumours, mostly exaggerated, swirled around Trondheim but the facts soon became clear: A Linge group, ‘WoodLark’, had placed charges on the railway lines near Snåsa, a German military train was destroyed, 70 soldiers were killed, another 200 wounded, two Norwegian railway employees died, and the line remained closed for a week. This sabotage made a big impression on the people of Trøndelag and discussions on the ethics of sabotage raged throughout the county. EGO summed up by writing: “The action at Snåsa clearly shows that people are enthusiastic about sabotage and the more it harms the Germans the better it is. On the other hand, they themselves prefer to be spectators – and at such a distance as not to be involved.”

Polar Bear 2 arrives

The long-awaited Linge groups that were to protect installations and industries against German destruction arrived in the middle of January 1945. ‘Polar Bear 2’ comprising Leif Hauge and Trygve Renaae were billeted with county-representative Cappelen. His two daughters became assistants and messengers. From ‘Lark’ they got 10 men and later, from Durham, another 50 men. They used ‘Lark’s’ radio and courier connections. One of the first messages sent by Hauge was that Rinnan must be assassinated. ‘Polar Bear 2’ was designated to protect the harbour area, ‘Crowfield’, which didn’t arrive until the end of April, was to guard industrial installations. Most of the personnel from ‘Durham’ merged with ‘Crowfield’ in the final two months.

EGO and his men itched to join the sabotage actions that they knew were occurring to the north and south of Trondheim. But as they had only a small supply of explosives their sabotage actions were what might be called minor irritants On Christmas Eve came a message they had been hoping for: “…arrange for organisation and instruction of groups outside Trondheim and Strinda …Objectives: Preparation of sabotage against German communications upon orders from here, and preparation for prevention of enemy destruction of our communications…” Even more encouraging was the message received from Crown-Prince Olav: “A warm thank-you to all at home for the sacrifice and devotion to duty shown in the past year, and to the home-forces my best wishes for Christmas and the New Year. I send you all my heartiest greetings in the hope and certainty that we shall soon meet on Norwegian soil.”

Sabotage

The Christmas Eve enthusiasm and joy were tempered by a new message that told them to restrict their activities to organising and training, and by the fact that they received no addition to their meagre supply of explosives. On February 4 they reported that the necessary groups and bases were in place but that they needed “…an additional 75 kg explosives.” A week later a dramatic message arrived: “Absolutely necessary to delay German transport by rail. Attack the railways soonest. Go for tracks and minor bridges…Use the explosives you have. We have asked Stockholm to send plastic.”

EGO wrote: “It was enough to make one weep. Finally, the order to get started had arrived and we still only had 5-6 kilo explosives – after weeks when supplies could have been delivered, by boat, air, or courier.” They calculated that every day they delayed a train one German battalion would be prevented from strengthening the defence of Germany. They calculated further that with their 6 kilos they could at best, delay transport for 48 hours. Two battalions delyed, not much, but worth doing!

They agreed that Bjørnaas and Wisløff should lead the Stjørdal group at Nyhus and EGO the group from Ler. The two former were among the most experienced Linge-men but EGO hadn’t set an explosive charge since his training days in Scotland – maybe he wanted to prove that he remembered his lessons. Their backpacks were heavy with explosives, fuses, and blasting caps as well as ammunition for the men they were to meet.

The men at Ler had received no advance warning but when EGO arrived, two men volunteered and within two hours they were on their way. At the tracks, one man stood guard while the other two laid the charges and lit the fuses. As they moved from one charge to the next the explosions began. Immediately shots rang out from a nearby German watch-post. But it was dark, the Nazis were firing blind, and the three saboteurs had no difficulty in disappearing into the forest. EGO had to wait two days before Bjørnaas and Wisloøff returned from Nyhus. They had completed their mission, but without the help of the Milorg group at Stjørdal.

On February 21 London advised that the Swedish authorities refused to allow transport of explosives, “pending negotiations.” The next day EGO sent disturbing news to London: State Railway informs us that the Germans have attached a ‘prison coach’ behind the locomotive of all passenger trains between Mo and Otta. Many previous home-front leaders used as hostage passengers – up to 20 men on each train. Shall we avoid de-railing or do current orders apply? Please reply soonest. The reply came promptly: “Train with hostages must not, repeat not, be de-railed.”

Disappointments

Throughout January and February, the lively radio exchanges between Trondheim and London continued. No radio contact could be made at night – probably because of frequency error or insufficient power – and the fact that London, after promising continuous, 24 hour listening, only tuned in at the old scheduled times. Promises of drops, requests for information about drop-zones and detailed procedure orders were other frequent exchanges, but no ‘special messages’ came on the BBC and no aircraft droned overhead. Towards the end of February, the liquidation of informers came back on the agenda. London had nothing against attempts to assassinate Rinnan and Rogstad. This message was addressed to ‘Polar Bear 2’ – but: “…you should not attempt to do this yourselves…. Can you delegate the job to a couple of reliable guys?”

It is not difficult to imagine why EGO lost his faith in London when he read this. He thought it inconceivable that they should ask ‘Polar Bear 2’ to find amateurs to do a job that had eluded some of the top Linge men in the country – especially when there were three trained Linge men, (Bjørnaas, Wisløff and himself), available in Trondheim who would jump at the chance to eliminate these criminals. Worse was to follow; Odd Sørli was replaced by Professor Lyse in the Stockholm office. He gave no reason for being replaced, and no information as to the where he was going, or when. EGO could not understand what had happened. Sørli had been his leader and friend right from the start and he knew ‘Lark’ and Trondheim better than most. On March 4th EGO suggested that he should take a trip to Stockholm. Two days later the OK arrived and on the 11th, EGO left Trondheim leaving Bjørnaas in charge of ‘Lark’. He was not allowed to return to Trondheim.

In Trondheim, with Bjørnaas in charge of ‘Lark’, operations continued along well-worn tracks. London continued to request intelligence, information about drop-zones and weather forecasts but no supplies, or men, arrived; except that two men were dropped without warning at one of the DZ’s. Were they Allies? Bjørnaas radioed for confirmation. “OK” came the reply, “Do not contact these men. They have nothing to do with our business.”

The Linge-groups ‘Polar Bear 2’ and ‘Crowfield’ integrated well with ‘Lark’ and ‘Durham’ though there were questions concerning command and rank. London was definite in a message to ‘Lark’: “In central Trøndelag the current leader of the organisation is Guttormsen (Magne Nordnes). You will work in collaboration with him. He ranks above operational leaders in district.”